The following essay was originally written in 2011 for a course I took called “The Anthropology Of Music”. In this course I learned about the theoretical perspectives that influence the field of ethnomusicology – the study of how and why people use music. An understanding of the diverse rubric of perspectives in this field helps me to enjoy music more than I previously did and more than I previously imagined. For example, at this point in 2014 I have been playing music over 47 years; since I was four years old. So, coming from a blues, rock and jazz background, I know how I learned music and I know how music and musical culture has been transmitted to me. A lot of that info is upcoming in future essays. I’m mentioning this because the rubric of my own understanding is more diversely illuminated since I began to understand the myriad of perspectives and approaches that ethnomusicologists employ. To put it another way, at heart I am a performing musician. I relate to sound from an emotional point of view. When I play music with others, the sounds others make evoke emotions and nature. When I hear the sounds others make, I am inspired to participate and communicate with them using my own sound. However, by understanding contemporary cultural anthropological methodologies and perspectives, I now enjoy communicating and participating with a lot more people who use and enjoy music in ways that are different than me.

Anthropology of Music – Reading Review #1

“What has characterized ethnomusicology most throughout its history is a fascination with, and a desire to absorb and understand, the world’s cultural diversity.” ~ Bruno Nettl (1991: xi)

In this review, three books from three time periods link the development of ethnomusicology with the world’s cultural diversity and reflect on the history of ethnomusicological and anthropological theory and practice. Published in 1964, after “some fifteen years of thinking and of discussion with colleagues”, Alan P. Merriam’s The Anthropology of Music elucidates an anthropological approach to conceptualize ethnomusicology (1964: vii). In 1991 Bruno Nettl’s and Phillip V. Bohlman’s, Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology (CMAM), provided the field with a collection of essays on the history of ethnomusicology and it’s methodological and theoretical foundations. In 2008 Ruth M. Stone published Theory For Ethnomusicology, an overview of the theoretical underpinnings of ethnomusicology. These works themselves are part of ethnomusicology’s history and disciplinary development as the evolution of the multi-dimensional paradigms used in the field is ongoing. Stone states, “The history of the field serves to illuminate the present situation” (2008: x). Stone observes that ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger (1886-1979) set a precedent for “present day ethnomusicologists to draw on multiple approaches…” (2008: xi). Similarly, Alan Merriam combined his academic studies to synthesize a scholarly approach to understanding music making. Early on, Merriam majored in music theory and composition while he also played and arranged jazz, graduating in 1947 from Montana State University. He finished his master’s degree in music with a thesis on jazz instruments from Northwestern and then received his doctorate in anthropology (Nettl 1982: 99). Merriam states in his landmark book, “there is an anthropology of music, and it is within the grasp of both musicologist and anthropologist” (1964: viii; emphasis in the original). He later established his objective “to provide a theoretical framework for the study of music as human behavior; and to clarify the kinds of processes which derive from the anthropological, (and) contribute to the musicological (1964: viii).

Additionally, Merriam reflects, “field method in ethnomusicology has derived from the social sciences in general, while field technique is borrowed most widely from the particular social science of anthropology” (1964:48). Nettl and Stone both subscribe to this multi-faceted approach stating, “a major characteristic of ethnomusicology in the United States has been its eclectic character and its tendency to sample from a variety of disciplines, theories, and approaches…” (Nettl 1991: 267). Furthermore, Stone mentions that, “aspects of what are described as a theory in ethnomusicology are often employed in conjunction with other theories” (Stone 2008: 37). Despite the fact that the content of these three texts primarily relies on traditional cultural anthropological methodologies, some of the theories that Stone explores, such as cognitive theory and postmodernism, are relatively new developments.

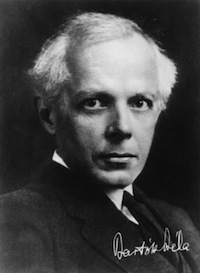

As Merriam states, “the roots of ethnomusicology are usually traced back to the 1880’s and 1890’s…” (1964: 3). In this early period, ethnomusicology’s antecedent was known as “comparative musicology”. Comparative musicologists include Bela Bartok, Erich M. von Hornbostel, and Andre Schaeffner (2008: 32-33).

Comparative musicology was predicated on cultural evolutionist assumptions (Stone 2008: 25). Among these assumptions was “the theory that all cultures are evolving to ever-higher states and some cultures have reached a more developed state than others” (2008: 25). Through borrowing cultural evolutionism and diffusionism theories, certain assumptions comparative musicologists made functioned as hegemonic precedents, thus differentiating “so-called high cultures from the so-called primitive cultures” (2008: 32). The flaws of these intellectual formulations limited the scope of research by processing the data of the “other” through the lens of the “superior” academic western bias. Consciously or not, comparative musicology’s elitist assumptions were blind to issues of race, ethnicity, class and gender. As these assumptions became decoded in academia, theoretical approaches, borrowed from contemporary cultural anthropological methodologies, helped to provide a more diverse rubric, which Merriam incorporated to conceptualize ethnomusicology.

The scrutiny of European hegemonic cultural perspectives within comparative musicology fostered new approaches, perspectives and theories for ethnomusicologists. Stone notes, “Theories often incorporate aspects from earlier approaches and thus build from earlier work” (2008: xii). Stone comments that her mentors Alan P. Merriam and Charles Boilés, “instilled a keen interest in and concern for theory…” (2008: xi). We learn that Stone’s work developed from her predecessors. Boilés taught a class called “Paradigms in Ethnomusicology” at Indiana University (2008: xi). By 1980, Stone had inherited the course and “expanded the course to include a broad range of theoretical approaches” (2008: xii, xi).

Through a historical lens, Stone’s book presents “views on the advantages as well as limitations of these theoretical approaches in ethnomusicology” (2008: xii). Stone’s topics, part of the contemporary rubric of cultural anthropology, include a variety of approaches such as structural, linguistic, Marxist, cognitive, performance theory, gender, ethnicity, and identity theories, and postmodern/postcolonial thought. Most of the fourteen chapters in Stone’s book are dedicated to a specific theoretical approach, methodically noting it’s history, contributions, critiques, and observations from other ethnomusicologists. Stone incorporates each respective theoretical approach with her own fieldwork and concludes each chapter with an extensive reference listing. Unlike the books by Merriam and Nettl, Stone also presents a variety of data in standard musical notation (2008: 64), musico-linguistic diagrams (2008: 65-80) and song lyrics (2008: 47).

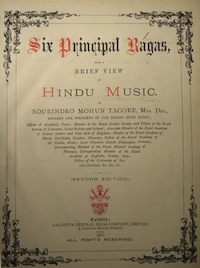

These three books link ethnomusicology’s history and disciplinary developments. Each book is a historical study employing participant observation. In CMAM, scholars from around the world present issues on the history and varieties of methodologies. Nettl observes that “as the national identities of scholars change, along with their ideologies and their relationships to the people whose music they study, the nature of the scholarship also changes” (1991: xi). Nettl contrasts Charles Seeger’s multi-disciplinary contributions with George Herzog (Nettl’s teacher) who “tried to establish a consistent methodology…with specific methods and techniques” (1991: 270). Dieter Christensen’s essay focuses on the merits and deficiencies of Hornbostel and Carl Stumpf and the institutionalization of comparative musicology. Charles Capwell distinguishes Sourindro Mohun Tagore as an influential nineteenth century Bengali scholar.

As gender issues have also been part of the history and the study of ethnomusicology, these texts note a variety of conflicts that have emerged in the largely patriarchal society. Charlotte J. Frisbee writes about the involvement, roles and contributions of women from the formation through the incorporation of the Society for Ethnomusicology, spanning the years of 1952-1961 (1991: 244-265). Frisbee notes ten women who “emerged as early worker counterparts” including Frances Densmore and Helen Roberts (1991: 245). More recently, Ruth Stone offers contributions and critique of feminist issues (2008: 145-148).

Reexamining or restudying fieldwork data can be beneficial for a variety of reasons as the revisiting of direct and/or indirect experience may more fully illuminate the array of theories. Merriam explains that one of the special problems that arise in field research concerns restudies, “in which an area or a problem is checked a second time by the same or by a different investigator” (1964: 51). In CMAM, Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy recounts a restudy of Arnold Blake’s fieldwork in India (1991: 210-227).

Both Jairazbhoy and Merriam discuss the challenges for conducting restudies including “lack of available personnel (and) limited funds available for field research” (1964: 52, 1991: 220). Stone doesn’t address restudy at all in her book.

Merriam is most effective in defining method and technique in the formative development of ethnomusicology (1964: 37-60), conceptualization about music in a variety of contexts (1964: 63-84) and behavior “in respect to the production and organization of sound” (1964: 103). Merriam is adept at providing background and insight on the process of composition and improvisation (1964: 165-184). Stone includes contrasting levels of approaches from a bird’s eye view and a jeweler’s eye view when phenomenology, linguistics, literary and dramaturgical approaches are investigated. CMAM’s format presents “greatly expanded versions of papers read at a 1988 conference” by nineteen scholars from five countries (1991: xii). The contextual diversification functions “as a way station to a comprehensive history . . . that shed light in a large number of ways on the development of ethnomusicology as it has come to exist in the 1980’s” (1991: xii). A distinguishing characteristic of CMAM, as Philip V. Bohlman points out in the Epilogue, “linking these essayists . . . is their common role as intellectual historians…” (1991: 356).

When working in concert, these three books compliment each other as reference works for the development and history of ethnomusicological and anthropological theory and practice. Perhaps they may be used together in a classroom as a graded tripartite model for the study of ethnomusicology. Each third of a class may be given the responsibility to teach sections of one book to the other two thirds. In a 90-minute class, where each third has 30 minutes to speak, each book may be addressed. In the next class, the three books may be exchanged amongst groups and the process is repeated thus allowing each group to teach from each book. This may be repeated several times.

Anthropological and ethnomusicological research continues to grapple with basic questions of human diversity and similarities. It seems natural to this author that the accumulation of data, from a variety of perspectives, is essential to strengthen the evaluation of a particular theory. As the body of evidence in any given specialization grows, ethnomusicologists have the opportunity to revise their interpretations, thus developing more insight for issues and our understanding of humans. Through studying the evidence of anthropological and ethnomusicological cross-cultural issues, we understand and recognize that each of us is part of one magnificently diverse human family that we all share.

Works Cited

Merriam, Alan P. 1964. The Anthropology of Music. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Nettl, Bruno. 1982. “Alan P. Merriam: Scholar and Leader.” Ethnomusicology 26/1: 99-105.

———, and Phillip V. Bohlman, eds. 1991. Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Stone, Ruth M. 1997. Theory for Ethnomusicology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles