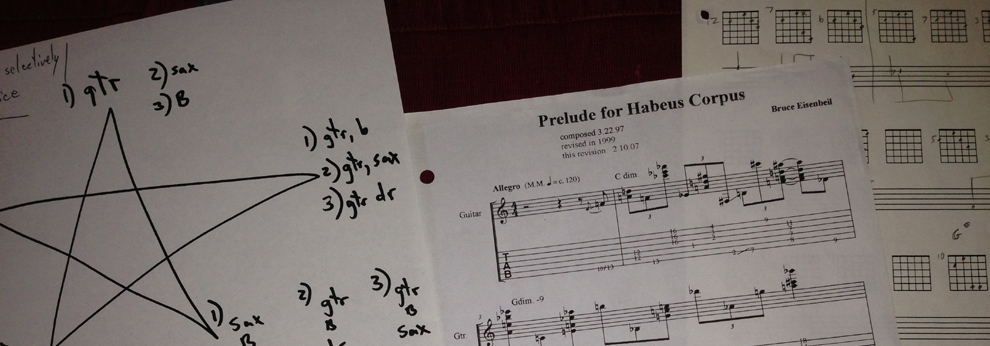

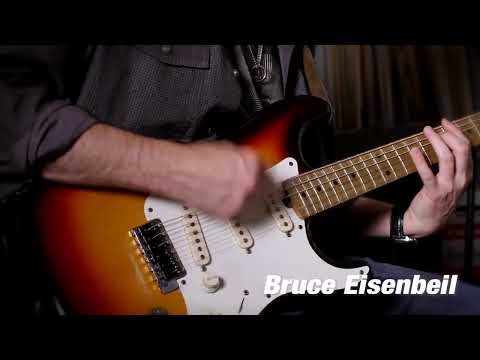

image by BE

In the winter of 2012 I took a course called “Critical Theory And The End Of Noise”. This post, a reading review, is the first of six papers from that heading which will be published here. These papers have been edited or modified since I originally wrote them. I added a few commas and tied some points together a little better than before. There is always more I could do, but my hero Bruce Lee is whispering in my ear , “If you spend too much time thinking about a thing, you’ll never get it done.” People get ready, a variety of high-brow and low-brow sources are cited. Sheesh, this essay runs the gamut from German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin, to French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist, critic, and semiotician Roland Barthes to French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, philologist and literary critic Michel Foucault to composer Edgard Varèse to French economist Jacques Attali to champion of experimental music Henry Cowell to French composer, musicologist and experimental electronic pioneer Pierre Schaeffer to music critic Simon Reynolds to pop singer Adele to prolific musician, writer and editor Merzbow. The street artist Banksy wrote, “Some people criticize me for using sources that are a bit low brow but you know what? ‘I’m just going to use that hostility to make me stronger, not weaker’ as Kelly Rowland said on the X Factor.” Thanks Banksy! Did you know that in 2013 my co-led trio TOTEM> released a CD called “Voices Of Grain”? Barthes and some other writers, but especially Barthes, sourced in the following paper, inspired that title. Thanks RB. By the way, some readers may not know that I was fortunate to study with composer Gheorghe Costinescu who received a Ph.D. with distinction from Columbia University and also received a Post-Graduate Diploma from The Juilliard School, where his main teacher was Luciano Berio. Berio was a student of Schaeffer. Toot Toot! Wooly Bully! A genealogical perspective is pursued throughout the following paper.

Reading Review #1 (part 1 of 2)

Noise is power. Avant-garde and experimental composers and performers use the veracity of Noise as a catalyst for musical inspiration and as an expression of power. Additionally, we shall see that Noise is a response to bourgeois authoritarianism. This essay is an overview that focuses on several texts including the introduction and Part One of an anthology of discourse on the terrain of experimental music in the vanguard for the past 100 years, Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music assembled by editors Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner; an essay that explores the history of the relationship between art and capitalism’s technological developments, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), by Walter Benjamin; and an essay that focuses on the dual relationship between music and language, “The Grain of the Voice” (1977), by Roland Barthes. Additionally, Michel Foucault’s perspectives on power and genealogy, as he himself defines the subjects in a variety of contexts will be referenced as Cox and Warner raise these perspectives in the introduction of Audio Culture as well as in the introduction of subsequent essays. Foucault wrote that power “reaches into the very grain of individuals, touches their bodies and inserts itself into their actions and attitudes, their discourses, learning processes and everyday lives” (Foucault 1980: 30). Finally, contemporary expressions of power, noise and grain will be referenced through the use of a modern pop song by the singer Adele and her recognition by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS); the governing body that produces the Grammy Awards and which has recently shrunk the scope of it’s musical vision.

Foucault has stated that the over arching theme of his life’s work is the concept of ‘power’. Although a variety of processes contribute to various orientations of power, it is not the objective of this paper to define each process or theoretical orientation. However, two concepts related to power are particularly relevant to this paper: “savoir” and “connaissance”. Foucault uses the word “savoir” [knowledge] as the transformational process that one (the subject) undergoes as he/she does the necessary work in order to learn about an object (Foucault 1994: 256). This is the studying process that opens a new door of perception so that one is equipped with a new ‘tool’, a new way of perception, a new ‘mode of consciousness’. Contrastingly, Foucault uses the term “connaissance” [knowledge] as the work one does to multiply the knowable aspects of a particular object in order to make that object more intelligible (256). It is for this process that he expresses the orientation of ‘archeology’, which is all the ‘digging’ one does for the construction of “connaissance” (256). In the realm of “connaissance” the person (the subject) maintains his/her ‘objectivity’ and rationality. From the realm of connaissance”, one may express their knowledge and thus express power.

The power of the transformational process of “savoir” may be perceived in Benjamin’s essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. Benjamin notes that the movie camera introduces the viewer to unconscious optics (48). For instance, with close ups, space expands and with slow motion movement is extended (47). Just as film may reveal entirely new structural formations of the object, the way that music is engineered and mixed may provide details about the primary and secondary themes or to put it another way, the foreground and background matter that the music is dealing with. Benjamin goes on to state that, “the history of every art form shows critical epochs in which a certain art form aspires to effects which could be fully obtained only with a changed technical standard, that is to say, in a new art form” (48). In essence, by emphasizing and putting forward images or sounds that are usually ignored, we have changed a technical standard and thus achieved a destruction of the aura of the original. Benjamin defines aura as “a phenomena of distance, however close it may be” (33). The outrage from the destruction of the aura is in itself a cause for wonder. As a consequence of the wonder, Benjamin notes that the shock of the new image is cushioned by a heightened presence of mind (49). The heightened presence is the Foucauldian concept of “savoir”. A parallel is found in music when composers give Noise value and use Noise as power for new music.

The power of the transformational process of “savoir” is the core of the genealogy of contemporary music. The editors of Audio Culture do not try to develop a history of contemporary musical practices. Rather, Cox and Warner link together various eras and cultures as coming from one genealogy. The genealogical perspective is documented by Foucault in “Nietzsche, Genealogy, and History”. Both Foucault and Nietzsche considered themselves “genealogists” and evidence of the latter’s work may be found in On The Genealogy of Morals. Foucault states, “It [genealogy] opposes itself to the search for “origins.” (Foucault 1984: 77). Genealogy is distinguished from more traditional forms of historical research in that genealogical studies do not strive to be chronologically linear and are not concerned with defining a beginning or an end. In the end, genealogy does not reinforce the bourgeois “myth of progress.” This essence of a genealogical continuum is corroborated by Benjamin when he states “the uniqueness of a work of art is inseparable from it’s being imbedded in the fabric of tradition” (Benjamin 34).

Noise is the source of power and purpose in music. In Chapter 1, “Noise and Politics”, Attali suggests that the appropriation and control of noise is a reflection of power and is political by nature (Cox and Warner 7). For Attali, “music, like economics and politics, is fundamentally a matter of organizing dissonance and subversion – in a word, ‘noise’” (7). Attali mentions that music is an attribute of panoply of power (7). The form that musical power takes may be as an object of consumption, a force for subversion, or meaningless noise (8). The political use of this musical force is similar to the above defined forms and definable by its characteristics. For example, characteristics common to totalitarian regimes include a concern for maintaining tonalism; the primacy of melody; a distrust of new languages, codes or instruments; and banning subversive noise because it demands cultural autonomy (8). Thus, subversive noise is a challenge to authoritarian power. This authoritarian power may be expressed by a multinational corporation, a smaller body such as NARAS which hosts the Grammy awards, or individuals who may exert their ego/will against new sounds in music. This author agrees with Attali’s assessment that for the most part contemporary music that is distributed by multi-national corporations is a disguise for the “monologue of power” (8). This has most recently been seen in musician’s protest of the removal of 31 Grammy categories.[i] The consolidation of power becomes more conspicuous with the photograph of Adele cradling her six Grammy awards.[ii]

However, Attali notes that despite the fact that music in the contemporary era is little more than an “excuse for the self-glorification of musicians”, music is an activity that is “essential for knowledge and social relations” (9).

Noise exists in the natural tone of all acoustic instruments. In Chapter 5, champion of experimental music, Henry Cowell, notes in his essay “The Joys of Noise”, “there is a noise element in the very tone itself of all our musical instruments (23).” As Cowell considers the sound of the violin, he notes that part of the vibrations producing the sound are periodic, although other vibrations do not re-form the same pattern, and “consequently must be called noise” (23). Additionally, Cowell states, “the use of noise in music has been largely unconscious and undiscussed” (24).

Noise is the ‘grain’ of the voice and with ‘grain’ the voice expresses power. Through an analysis of language’s relationship with music, semiotician and post-structuralist Roland Barthes illuminates a musical semiology in his essay “The Grain of the Voice”. Barthes notes, “The ‘grain’ is that: the materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue . . .” (95). Barthes goes on to state that in vocal music, the diction of the language is expressed in the ways that the melody explores how the language works and simultaneously identifies with the language (96). In this way, the melody plays with the “voluptuousness of its sounds-signifiers” (96). Barthes goes on to state, “What is difficult is for the body to accompany the musical diction not with a movement of emotion but with a ‘gesture-support’; all the more so since the whole of musical pedagogy teaches not the culture of the ‘grain’ of the voice but the emotive modes of it’s delivery; the myth of respiration” (96). In this case ‘culture’ means ‘nurturing’ and thus Barthes believes that vocal pedagogy is misguided in what it chooses to nurture. Barthes is clear to note that ‘grain’ is not merely the timbre of the voice (98). More to the point, ‘grain’ “cannot better be defined indeed than by the very friction between the music and something else, which something else is the particular language (and nowise the message)” (98). It is this friction that is the voice’s expression of noise and thus an assertion of power. Grain is the sonic friction to the homogeneity of pitch color regardless of register. Noise is the body’s natural and individual rebellion against homogeneity. Ultimately, Barthes notes, “the ‘grain’ is the body in the voice as it sings…” (100).

Noise is the source for new sounds and thus new music. Edgard Varèse felt that the most original past masters had a desire in common to create new sounds. In their own respective eras, these new sounds were construed as noise. This is the genealogy Varèse traced and with which he participates. In Chapter 4, “The Liberation of Sound”, Varèse notes, “anything new in music has always been called noise. But after all, what is music but organized noises?” (20). This led Varèse to redefine music as “organized sound” (17). He notes that new sounds, such as electronics, are “additive, not destructive” to the accepted musical palette and should not be construed as a threat to the establishment (19).

Part 2 of this essay, along with end notes and bibliography, will be posted next week.

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles