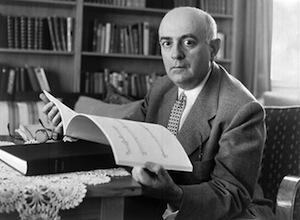

Does music change when new musical practices and new technologies emerge? Does subversion and transgression uproot the tyrannical weight of cultural memory? This is the second post in this heading, “Critical Theory And The End Of Noise”. We are going to explore the thoughts and perspectives of some new and old friends. Look out below! because we are going to interact with Canadian philosopher of communication theory, public intellectual and fixture in media discourse – Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980); Austrian composer, longtime Bertolt Brecht associate – Hanns Eisler (1898-1962); one of the foremost continental philosophers of the twentieth century,sociologist, philosopher and musicologist known for his critical theory of society – Theodor Adorno (1903-1969); innovative French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist and acoustician – Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995); Spanish avant-garde experimental musician and sound artist – Francisco López (1964); Swedish musicologist, researcher, writer, music critic – Ola Stockfelt (1953); English musician, composer, record producer, singer, visual artist, and one of the principal innovators of ambient music – Brian Eno (1948); author and Professor of Cultural and Postcolonial Studies known for his interdisciplinary and intercultural work on music, popular and metropolitan cultures – Iain Chambers (1949); American composer, accordionist, author, and music professor who is a central figure in the development of experimental and post-war electronic art music – Pauline Oliveros (1932); and American composer, music theorist, early adapter of electronic music, and Professor of Music Emeritus at Princeton University – J.K. Randall (1929-2014).

Reading Review #2

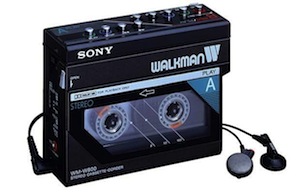

As new musical practices and technologies emerge, it is necessary to develop a new discourse about listening conventions because changes in music production and the reception of sound have caused a shift in the definition of “music”. This paper is an overview that focuses on several essays published in an anthology of discourse on experimental music, Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music assembled by editors Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner. From Audio Culture we will explore the writings of Marshall McLuhan, Hanns Eisler, Theodor Adorno, Pierre Schaeffer, Francisco López, Ola Stockfelt, Brian Eno, Iain Chambers, Pauline Oliveros, and J.K. Randall. Contemporary modes of listening is the ontology that is explored by these writers. This rubric may have begun with the concurrent development of the phonograph and telephone. However, later modes include the radio, tape recorder, television, satellite, cassette recorders, Walkmans, Compact Discs, the Internet, Skype, mp3 players, iTunes, and Pandora. Each essayist explores similarities and differences in this ontology. Furthermore, each writer’s epistemological inquiry describes how contemporary sounds are acquired and realized. In addition, the perspectives investigated by Cox and Warner will be supplemented with a contemporary perspective of parody, A Theory of Parody – The Teachings of Twentieth –Century Art Forms by Linda Hutcheon. When used as a post-modern recoding, parody is an important mode of coming to terms with the texts and discourses of the past without the connotation of satire’s ridicule.

New listening conventions arise to compliment and provide balance with the vast spectrum of visual forms of stimulation. In his essay “Visual and Acoustic Space”, Marshall McLuhan examines the ways in which communication and information technologies transform human community and subjectivity.

His concept of “the global village” – a world network of electronic media – anticipated the Internet by two decades (2010: 67). McLuhan notes that compared with the visual sense, the auditory sense in western man is under-stimulated which can cause thought and feeling to separate (69). Over reliance on linear conceptualization and the desire for sequential relationships overpowers other modes of logic. McLuhan notes that pre-literate and post-literate humans primarily rely on acoustic phenomena out of preference and for survival. This type of imagination is discontinuous and non-homogeneous as the centers are everywhere and the boundaries are nowhere (71). McLuhan explains that the uniform ethos of written language has dominated western man’s consciousness after the oral tradition in early Greece (68). McLuhan quotes neurosurgeon Joseph Bogen who regards the linear sequential mode of the left hemisphere of the brain with language and analytical thought. Alternatively, the right hemisphere of the brain deals with abstract pattern recognitions that are not wholly sequential (69). Not only are new audio technologies complimentary with the interplay of the plethora of visual modes, but they are also necessary for the development of our brain’s two hemispheres to be psychically united (72).

When combined with film technologies, sound and music may transform the linear narrative that at its core has a dulling effect on the senses. In their article “The Politics of Hearing”, Hanns Eisler and Theodor Adorno make the case that the ear of the layman is indefinite and passive (74). The fact that one does not have to open it, unlike one’s eyes, makes the ear apathetic and dull.

This point of view has something in common with McLuhan’s previously mentioned perspective that western man’s auditory sense is under-stimulated. Adorno and Eisler state that avant-garde music serves as one of the few forces of resistance to “the culture industry.”(73). Music is supposed to bring out the spontaneous, essentially human element in its listeners and in virtually all human relationships (74).

Adorno and Eisler make the case that music as art has an objective to transform the indolence, dreaminess and dullness of the ear into a matter of concentration, effort and work.

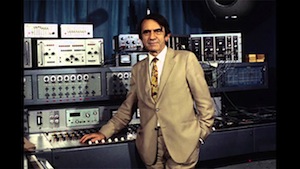

New conditions of observation are developed through new mediums and technologies that transmit recordings. In his paper “Acousmatics”, Pierre Schaeffer is fascinated by the fact that radio and recording make possible a new experience of sound.

He calls this “reduced listening” or “acousmatic listening”. This approach discloses a new domain of sounds or new sonorous objects (76). Schaeffer is influenced by the philosophy of Edmund Husserl, founder of “phenomenology”. Phenomenology disregards the traditional distinction between subject and object or appearance and reality. Phenomenology attempts to describe the contents of experience without reference to its source and without regard to the subjective mode (dreaming or waking) (76). With respect to music, phenomenology attempts to describe the differences among sounds themselves (76). The sounds themselves – the sonorities – become a sonorous object and they have their own existence distinct from their sources. Sonorous objects can be clearly described and analyzed (81). As each new recording creates new phenomena to observe we can gain knowledge from them and we may transmit this knowledge (81).

New listening conventions may be integrated with new recording technologies. In his essay “Profound Listening and Environmental Sound Matter”, Francisco López integrates Schaeffer’s concept of “acousmatic listening” with the largely unseen sounds of the rainforest such as those made by birds, insects, and monkeys (82). López’s recordings of these sounds are mostly “untitled” in an effort to focus the listener’s attention to the sounds themselves rather than to their sources (82). López explores the use of parody by appropriating René Magritte’s painting, This Is Not A Pipe (85). Hutcheon notes Magritte’s form of parody is a response to medieval and baroque emblems with an accompanying title or motto (2000: 2). López’s album title This is not La Selva: Sound matter vs. Representation, recodes Magritte’s work (85). Here, the use of parody challenges the difficulty of music, in contrast to painting, to convey meaning. López makes the distinction that the musical piece titled La Selva is not a representation of the reserve in Costa Rica, La Selva. López states that La Selva, the recording, features nature sound environments [NSE](84).

Recording and mixing techniques that do not manipulate one’s perception of foreground or background distinguish NSE recordings. The resulting recording is “not arranged purposefully but emerges incidentally, due to the microphone location, placement and directional pattern; somewhat similar to a pair of human ears” (83). The rainforest offers a cornucopia of sound matter that may not be music in the classical sense though the focus on sound matter certainly expands and transforms “our concept of music through nature” (87). In this way, asking ‘how is this music” or “why is this music” reminds this author of McLuhan’s essay where he notes that anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski and Dorothy Lee, who studied the Trobriander Islanders, found that Trobriander culture disdained the concept of why (70). Malinowski and Lee note that the Trobriander are only interested in experiencing the current essence of a person or object (70). The Trobriander does not look for patterns of cause and effect, nor is the Trobriander interested in setting up a hierarchy of priorities (70). In this way, the Trobriander directly experiences a sense of timelessness (70). López notes that in order to attain a musical state of profound listening one must listen to the sound matter from the inside (87).

As new audio technologies emerge, previously heard music and sounds evoke new meanings and must be reconstituted. In his commentary “Adequate Modes of Listening”, Ola Stockfelt recognizes that modern life requires us to cultivate a variety of modes of listening (88). The nature of a musical work is in flux as it is recomposed through different listening practices (88).

For example, the use of Mozart’s 40th Symphony in a James Bond film may designate an environment or social class.

Contrastingly, sitting in traffic with the same symphony loudly playing on the radio may cause anxiety (89).

In each of these situations, the music is “conditioned” based on the environmental encounter. Stockfelt articulates that western industrialized nations are dominated musically by ‘art music” and popular music. People experience music in almost every public and private living space. What constitutes music is learned and reinforced in everyday situations. Stockfelt explains that at every instant in the day, some sounds are clustered together and understood as music and other sounds are considered something else (89). Stockfelt does not mention what that something else is. Stockfelt believes that the mass media musical mainstream transcends traditional culture, class and age boundaries (89). I’m reminded that sociologist, anthropologist, philosopher, and renowned public intellectual Pierre Bourdieu wrote, “Nothing more clearly affirms one’s ‘class’, nothing more infallibly classifies, than tastes in music” (1984: 18). However, Stockfelt is most interested in philosophical hermeneutics, not sociology (2010: 88).

As new technologies appropriate new musical practices, a revised listening convention may influence new developments. In his article “Ambient Music”, Brian Eno describes how he acquired and came to use his music. Intrigued with the possibilities of environmental music but dissatisfied with the commercial appropriation of the concept by the Muzak corporation, Eno defined the emerging musical genre on his own terms (94). Eno describes his music as “ambient music” (94).

Eno notes that people he spoke with wanted “particular and sophisticated choices”. These choices would define the “sonic mood” of their home or workplace. Consequently, Eno chose music for its “stillness, homogeneity, lack of surprises and lack of variety” (94). Additionally, Eno emphatically mentions that a distinguishing characteristic and primary focus of Ambient music was the creative invention of new sounds and sound combinations (95). Besides using the natural reverberation of an environment, Eno became enamored with supplementing his recordings with artificial reverberation, homemade echo units and overdubbing. The implementation of sound-shaping and space-making devices helped Eno create new sonic worlds (95). Lastly, Eno’s phenomenological interest is to be immersed in the sound as his desire is to make “music to swim in, to float in, to get lost inside” (95).

New technologies that bring about new listening conventions may empower and transform listener’s inner selves along with the perception of their collective environment. In his paper “The Aural Walk”, Iain Chambers explores his particular interest in the circulation of music and its role in the construction of identity (98).

This essay considers the transformation of listening practices made possible by new technologies such as the Walkman (98). Chambers argues that one’s use of a Walkman empowers the individual to transform their personal experience of a public environment. Chambers notes that an urban environment has a vast array of sounds that may bombard an individual at any given time. An individual who listens to a Walkman while getting around the city, Chambers remarks, is akin to a city within a city. Additionally, the use of a Walkman allows one to be involved with the essence of technology (100).

New listening conventions incorporate all sound matter as useful in the compositional process. In her article “Some Sound Observations”, Pauline Oliveros lets the reader in on her process of listening and how this process is central to composition.

Oliveros fosters a holistic listening perspective that may include all sound matter in a non-hierarchical fashion. Oliveros’ concept of “Deep Listening” has traits in common with Adorno’s and Eislers concepts mentioned earlier with respect to music being a “matter of concentration, effort and work”. More will be written about “Deep Listening” in a future essay. However, as I read Oliveros’ essay “Some Sound Observations” and sit here trying to compose an essay I’m reminded it is 7:30 am because, like an alarm bell, the construction next door has just begun. Like it did yesterday. Like it has everyday for the past year. I’m not exaggerating. The construction has been going on for a year, literally, outside my window. The crew is out there seven days a week. Today they are working on the roof. Hammering rhythms: 12345; 12345678910; slowly now 1-2-3-4, rest, 1-2, rest, 1, rest; 1-2-3-4-5-6, rest; 1-2, rest; a plumber is banging a pipe into place. A piercing but hollow D4 pitch resonates with the rhythmic impact of 1-2-3-4-5-6-7. My wife stirs her coffee in the next room: clink clink clink clink clink. The construction started five years ago when a prominent real estate lawyer bought a six story building two doors away from the apartment I live in, for a measly $4 million. He spent a year and $2 million of his piggy bank change renovating the palace. I wasn’t invited to the open house party. Were you? A year later he bought the building next door with the intention to join these two brownstones and turn them into one inconspicuous castle. It turns out the second building had so many structural code violations that he decided to gut it right down to the bare brick walls. The primary issue though is reinforcing the foundation. The house is sinking. Manhattan wasn’t always this wide. Much of the east side is fill. I don’t know what it’s full of but that’s not the objective of this paper. Anyway, reinforcing the foundation meant some serious jack hammering. Fortunately city codes restrict the hours of this concussive force. You can’t start before 8am. But for some, paying the fine is preferable to construction delays. Oh well. A years worth of free wake up calls. During the months of jack hammering I became finely attuned to the rhythm, tones and dynamic range of the jackhammer. What is the dynamic range of the Jack Quartet when they perform Tetras by Iannis Xenakis? The pneumatic jackhammer has a variety of sonic phenomena including consistent rhythmic patterns ranging from two to uncountable numbers of attacks; attacks that can go on for three minutes uninterrupted. The jackhammer produces 100db of sound at two meters. The fundamental thud has a jangling metallic play, and the motor has a variety of whirring frequencies that extend to at least 15,000Hz. My wife blows her nose. I like that sound, especially when done by contemporary trumpeters. What was the first trumpet I ever heard blown? What was the first nose I ever heard blown? Was it my own? In the iTunes store, there are no entries regarding “blown noses”. Ditto for the Schwann catalog. A diesel generator has begun a new rhythmic dance. Streaming in from the window nearest my right ear, the pulse is a hyperactive, train-coming-off-the tracks 320 beats-per-minute and the frequency is coincidentally one octave below the pitch of my wife’s hairdryer which I hear in my left ear coming from the next room. Other music streaming in from the ambient jungle (secretly I hope that you pick up on my allusion and conflation of Eno’s “Ambient Music” and López’s NSE recordings) includes a car horn, a police siren, and a demonstration march at Dag Hammarskjöld Plaza that moves towards the U.N. Unfortunately, I don’t get around much anymore. It takes a bit of prodding from my wife to get me to walk with her to Central Park. It’s a great place to compose myself, in the vein of J.K. Randall, you know (look out below). You have to get inside the park to get inside the quietness of New York City; another way of hearing the sound matter from the inside as López noted in his essay. Despite the quietness, I can feel and hear the cities hum. However, it is the gentlest rustle of a leaf, in a tiny breeze, at a sound pressure level of 1 dB that captures me; but I digress.

In his essay “Compose Yourself “, J.K. Randall notates a phenomenological state of mind that refuses to separate the object from the subject. It is a style of writing that I admire because the thoughts ARE feelings.

The thoughts are not separate from feelings. This essay is akin to a stream of consciousness. The stream is Randall’s emotional and intellectual associations with the sound object – a recording of Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung.

In the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, listening conventions have changed as new musical practices and technologies emerged. In some cases, new musical practices have developed with new listening conventions. Hutcheons states that contemporary art and music is haunted by the tyrannical weight of cultural memory (2000: 5). The struggle to become an individual, free from the tyrant, is expressed through subversion and transgression. On the journey of the metamorphosis of the spirit, one may slay the Nietzschean dragon that demands “Thou Shalt” through incorporation and inversion of perceived cultural tyrannies.

Bibliography

Attali, Jacque. Noise – The Political Economy of Music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985. Print.

Bailey, Derek. Improvisation – It’s Nature and Practice in Music. New York: Da Capo Press, 1980. Print.

Barthes, Roland, “The Grain of the Voice.” Philosophy of Media Sounds. Ed. Michael Schmidt. New York: Atropros Press, 2009. 93-102. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Philosophy of Media Sounds. Ed. Michael Schmidt. New York: Atropros Press, 2009. 27-63. Print.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984. Print.

Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1973. Print.

Cox, Christoph and Daniel Warner editors. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum, 2010. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History.” The Foucault Reader: Ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon, 1984. 76-100. Print.

Foucault, Michel. Power. Ed. James D. Faubion. New York: The New Press, 1994.

Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Trans. Colin Gordon et al. New York: Pantheon, 1980. Print.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000. Print.

Nietszche, Friedrich. “Thus Spoke Zarathustra: First Part.” The Portable Nietzsche. Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Penguin, 1982. 138-139. Print.

Schmidt, Michael ed. Philosophy of Media Sounds. New York: Atropros Press, 1996.

Schoenberg, Arnold. “Opinion Or Insight?” Style and Idea. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1975. Print.

Solomos, Makis. “The Unity of Xenakis’s Instrumental and Electroacoustic Music: The Case for “Brownian Movements””. Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Winter, 2001): 244-254. Print.

The JACK Quartet: Xenakis String Quartets. Dir. Tim Chu. Perf. The JACK Quartet. Mode, 2008. DVD.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles