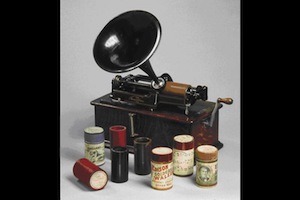

Edison phonograph and wax cylinders from the collection of ethnomusicological recordings at the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv

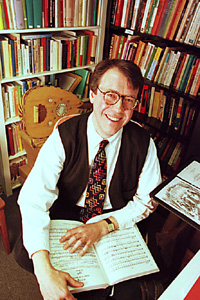

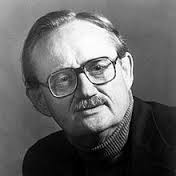

This is the second post in this heading. In this essay we are going to learn about the perspectives of some of the most influential theorists who helped to conceptualize the modern field of ethnomusicology including Alan P. Merriam, Bruno Nettl, Phillip V. Bohlman and Ruth M. Stone. The Society Of Ethnomusicology (SEM) has an annual conference which I attended in 2012 when it touched down in Philadelphia. While at the conference I was fortunate to hear many interesting academic lectures. Additionally, I was honored to meet Bruno Nettl and Ruth Stone.

Reading Review 2 – How Do We Know What We Know?

This reading review focuses on three texts: an anthropological approach to conceptualize ethnomusicology, The Anthropology of Music by Alan P. Merriam; a collection of essays on the history of ethnomusicology and it’s methodological and theoretical foundations, Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology (CMAM) by Bruno Nettl and Phillip V. Bohlman; and a contemporary overview of ethnomusicology’s theoretical underpinnings, Theory for Ethnomusicology by Ruth M. Stone. This paper has two primary objectives. The first is to look at the ways that these books specifically relate the history of anthropological theory to that of ethnomusicological theory. The second is to see how these works convey this relationship to the reader and to recognize how closely intertwined the two fields are.

Ethnomusicologist, musician and author, Philip V. Bohlman remarks, “Seeing ourselves in the Other and the Other in ourselves” is one of the primary motivations of anthropology (CMAM: 142-43). Beginning with Alan Merriam’s work, the same could be said of contemporary ethnomusicologists. Published in 1964, Merriam’s groundbreaking book strives to define the then relatively new field of ethnomusicology through the perspectives of cultural anthropology. This discipline was employed as a way to distinguish ethnomusicology from its predecessor, comparative musicology. In his various essays, Merriam’s use of cultural anthropological perspectives functions as his framework for the study of music as human behavior. Although his approaches were derived from anthropological perspectives, they contribute to the musicological and in turn, inform each other, thus synthesizing the field of ethnomusicology. Merriam’s objective is to establish frameworks of theoretical orientations in preparation for fieldwork processes. Both CMAM and Stone’s book concur on this method of development, implicitly and explicitly respectively (Stone 2008: 11). Some early approaches have become obsolete. For instance, Merriam’s appropriation of the anthropological structural functionalist approaches of Bronislaw Malinowski and most directly Alfred R. Radcliffe-Brown (Merriam 1964: 211) are now seen as too narrow as structural functionalism limits the research of any one aspect in detail (Stone 2008: 44). Being for the benefit of contemporary ethnomusicology, Stone defines a variety of contemporary anthropological frameworks specific to linguistics, postmodernism, sociological phenomenology, existential phenomenology, Marxist theory, communication theory, performance theory, cognitive theory, gender theory, post colonial and global issues, and historical research.

Merriam addresses method and technique noting that method depends upon theoretical orientation, basic assumptions that are aligned with the discipline, and the necessity for the ethnographer to notate his/her biases, partialities and predilections at the outset (Merriam 1964: 37-60).

His assumptions that ethnomusicology aims to approximate the scientific method, that the results of fieldwork and lab work be fused in the final ethnography, and that field method remain essentially the same through disparate cultures, is advanced by Nettl, Bohlman, and Stone. However, his third assumption regarding regional locales where fieldwork should be conducted has been challenged and revised. Context has broadened over the decades to include any community or culture. In contemporary ethnomusicology, not only is the study of Western and non-Western music ongoing, but popular, and vernacular music styles are also being studied. Stone’s book has a variety of examples citing work done in jazz communities (Stone 2008: 11, 19, 120, 158-159), as well as issues specific to ethnicity, gender and identity (2008: 145-164). Additionally, issues specific to field technique, the day-by-day solution of data accumulation, remain essentially the same although there have been significant technological advances in audio/video recording since the 1960’s. With regard to fieldwork recording, many of the early initiatives of ethnomusicologists and their forefathers were tied to the advent of audio recordings. Their motives were related to the salvaging of music that they feared would disappear with modernity (Diamond 2008: 33). Historical recordings include Jesse Fewke’s recording of Passamaquoddy Snake Dance songs, song transcriptions by Carl Stumpf, Benjamin Gilman’s Hopi recordings, Alexander Cringan’s Iroquis wax cylinders, and the thousands of recordings made by Frances Densmore (2008: 33). Erich M. von Hornbostel developed an extensive world music archive, serving as the first director at the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv from 1905-1933 (CMAM 1991: 201-09). Audio recordings are another ‘process of representation’ that serves to “transform observations into meaningful data, theories, and ideas shared by a community of ethnomusicologists (1991:136-37).” Audio recordings have been supplemented by other technologies including the melograph and timbre recognition by spectrum analysis. Historical accounts in CMAM also serve to illuminate oversights and mistakes in field technique that may enlighten and better inform contemporary ethnologists (1991: 210-27). (For a more in-depth study of these modern advances see this previous Blog Essay.)

Another approach of ethnomusicological theory includes linguistics. As evidenced by the work of Bartók and Kodály, comparative musicologists devoted attention to linguistic orientations as applied to the study of music. Additionally, George Herzog investigated relationships between language and music (Stone 2008: 51, CMAM 1991: 272).

Later on, linguistic approaches and semantic theories developed by anthropologist Leslie White and philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Susan Langer, influenced Merriam to study music as symbolic behavior.

This author finds that Merriam’s use of Carl Jung’s statement “the so-called primitive mind always operates in a state of reduced consciousness…” seems problematic, as it appears that Merriam may agree with Jung (Merriam 1964: 258). In CMAM, Albert Schneider looks at “Psychological Theory and Comparative Musicology” and organizes a variety of obsolete biases (1991: 293-317).

With regard to aesthetic criteria, an approach Merriam sought to incorporate, Merriam cites three philosophers Katherine Everett Gilbert, Helmut Kuhn and Thomas Munro (Merriam 1964: 259). Merriam takes up the study of aesthetics in the arts as a way to see if Western aesthetic concepts can be transferred and applied to other world societies (1964: 259). He cites six factors to consider, and although his findings are inconclusive, he sees ethnomusicologists as being in a position to contribute to further understanding. Stone outlines contemporary perspectives specific to cognitive theory and phenomenology that focus more directly on the six factors Merriam postulates (1964: 261-270).

This author believes that the three texts explored in this paper convey the relationship between the histories of anthropological theory to that of ethnomusicological theory through an epistemological lens. This realization arrived while this author read the epilogue of CMAM where Philip V. Bohlman describes the self-critical and self-reflexive preoccupation of the field (ethnomusicology) as a corollary of historical epistemology (357). The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy states, “epistemology is about issues having to do with the creation and dissemination of knowledge in particular areas of inquiry.” The overarching question asked throughout history by ethnomusicologists seems to be, “How do we know what we know?”[1] The nature and scope of knowledge is conveyed after a process of inquiry has occurred. From this process of inquiry, cultural anthropological perspectives inform the ethnomusicological discipline.

Ethnomusicology is inextricably intertwined with cultural anthropology. With the evolution and growth of ethnomusicology, more perspectives and their associative assumptions became part of the ethnomusicological lexicon. Each text in this paper explores anthropological and ethnomusicological truths, beliefs, justifications and how knowledge is produced. Additionally, skepticism illuminates issues that need further clarification, are found to be inconclusive, or have become obsolete. The multitude of approaches that ethnomusicology has historically embraced enhances research skills and one’s ability to understand and communicate with diverse cultures. Reviewing the history of cultural perspectives and theoretical underpinnings that have been used by ethnomusicologists causes this author to wonder about other means of understanding that may be emerging contemporaneously. New technologies combined with new perspectives may intertwine to produce a new, more meaningful, musical ethnography. New processes of representation may reveal more about the intellectual history of ethnomusicology.

END NOTES

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistemology, accessed December 6, 2011.

WORKS CITED

Diamond, Beverley. 2008. Native American Music in Eastern North America: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Merriam, Alan P. 1964. The Anthropology of Music. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Nettl, Bruno and Phillip V. Bohlman, eds. 1991. Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Steup, Matthias, “Epistemology”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), accessed December 6, 2011. Forthcoming URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/epistemology/>.

Stone, Ruth M. 2008. Theory for Ethnomusicology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

###################################################################################

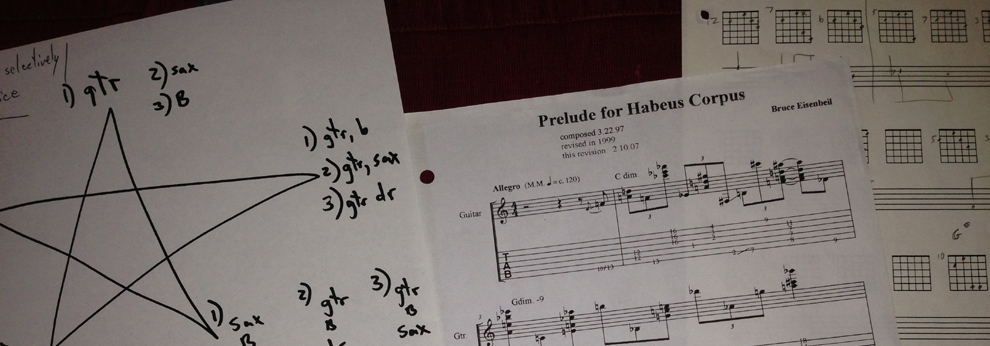

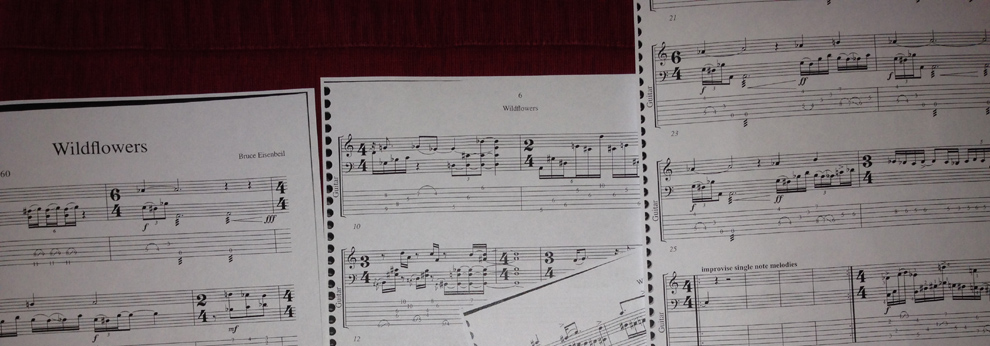

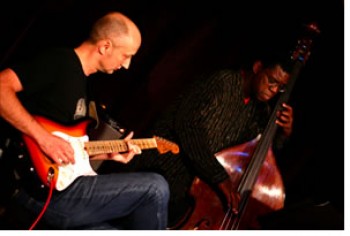

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles