What does blues, bebop, improvisation, Science fiction, soap operas, Carousel, and Sigmund Freud have in common? They are all subjects found in Ornette Coleman’s music which has inspired me since I was a teenager in the late 1970’s. However, I was introduced to Ornette’s music through my study of jazz guitar. Fortunately a good friend’s older brother had a treasure trove of ECM records that he encouraged me to listen to. One record I borrowed, and bought soon afterwards, was Pat Metheny’s “Bright Size Life”. I did my best to learn most of the songs on that record including his covers of Ornette Coleman’s “Round Trip” and “Broadway Blues”. So, I feel that Metheny introduced me to Ornette’s music. Thanks Pat! Then I got some of Ornette’s records and learned from them. After I moved to NYC in 1996 I met Ornette. It’s been an honor to get to know him and play music with him many times at his home. Sometimes with a band and several times for many hours playing duo. He is a very generous person and I can’t thank him enough for the experience, insight and inspirations he has shared.

In the essay below, the music of Ornette Coleman’s output will be read against Linda Hutcheon’s A Theory of Parody – The Teachings of Twentieth Century Art Forms. As you may recall, Hutcheon’s work has been covered here before. A few weeks ago I reviewed Hutcheon’s book. You can read that review HERE . In this review I note, “Hutcheon details the range of intent in contemporary parody, distinguishing characteristics illuminate it’s nature in contrast to allusion, burlesque, pastiche, plagiarism, quotation, satire and travesty. Hutcheon’s book is a reconsideration of both the nature and the function of parody. Hutcheon identifies contemporary parody as a unique theoretical perspective that intersects with invention and critique as a way to deal with the texts and discourses of the past. Parody is a dialogue with the forms of the past, a dialogue that re-circulates rather than immortalizes. In this way, parody expresses it’s genealogical function.” If you are struggling with accepting a contemporary understanding of parody, go to the above link and read the book review or , better yet, read Hutcheon’s book.

In the following essay, I consulted the work of a variety of writers including Jon Pareles, Ben Ratliff, Ethan Iverson, Amiri Baraka, Valerie Wilmer, Lewis Porter, Howard Mandel, Pierre Bourdieu, Ekkehard Jost and others.

This is the last post in this heading. I welcome your thoughts, impressions and suggestions on this post and/or the series.

Parody In The Music of Ornette Coleman

The music of saxophonist Ornette Coleman employs parody as a means for composition and improvisation. Coleman’s modern use of parody is a transformative creative expression that has similarities with other art forms and music due to its links with traditions. As Coleman transforms traditions to suit his pioneering nature, we recognize expressive creativity combined with critical commentary. For the purposes of this essay, the music of Ornette Coleman will be read against Linda Hutcheon’s A Theory of Parody – The Teachings of Twentieth Century Art Forms. Hutcheon identifies contemporary parody as a unique theoretical perspective that intersects with invention and critique as a means to interpret the texts and discourses of the past.

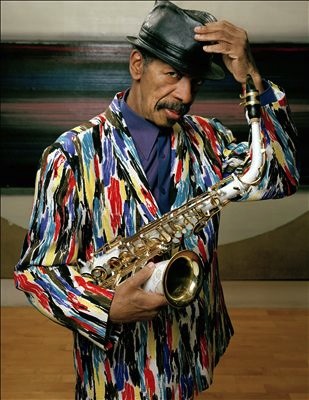

Knowledge and power interact in historical and social contexts to produce new paradigms for interpreting the world. These paradigms may shift over time as new players exert their own knowledge and power. Internationally noted UK writer and photographer, Valerie Wilmer, who specializes in jazz, gospel, blues, and British African-Caribbean music wrote, “Ornette Coleman is probably the most influential figure to emerge in African-American art music since Charlie Parker” (Wilmer 70).

Using various types of parody, both Parker and Coleman transformed and revitalized expressive musical paradigms.

In this essay, modern parody is the lens through which Coleman’s musical phenomena is perceived, interpreted, and given meaning. A variety of musicological and sociological perspectives may be used as a lens in order to interpret the function and “meaning” of music. Music has many constituents including the sociological and phenomenological context in which it is created.

For instance, as social critic Amiri Baraka points out, Coleman’s attitude is real and even though his emotional attitude is different than Mississippi Joe Williams, Snooks Eaglin or Lightnin’ Hopkins, “all of these attitudes are continuous parts of the historical and cultural biography of the Negro in America” (Baraka 15). Baraka goes on to say that the notes Coleman plays mean something and “that” something is “part of the black psyche as it dictates the various forms of Negro culture” (15). A synergistic interdependence exists that includes the musician’s worldviews, context, ethnicity, gender and socio-economic environment. Just as multiculturalism, post-modernism, and feminism have challenged former perspectives about knowledge, interdisciplinary approaches integrate theoretical perspectives from formerly separate fields to form a more complete framework for examination. Additionally, writer David Such notes that ideological issues may shape a musicians style of musical performance (12). Although parody has a hermeneutic function with both cultural and ideological implications (Hutcheon 2), it is not the objective of this essay to deeply explore one, or another, of the above cultural perspectives.

Traditional questions applied to the phenomena in Ornette Coleman’s music have led to misreading and failed communication. As a composer and improviser, Coleman asks other kinds of questions which open up new meanings. Coleman’s music often reflects on previous music of others and sometimes his own earlier work. Through reflection, Coleman reworks preceding music. Hutcheon notes, “a major way that music can comment upon itself from within …is through parodic reworkings of previous music (3).

Hutcheon defines two different types of parodic reworkings. Each type has different meanings. The first type of parody in music, quotation, is the superimposition of melodies, themes, chords and any other brief, but strong, identity marker of another composition. This is a more traditional type of parody. This type is not a global reworking that fuses old and new elements. Hutcheon notes that jazz artists such as Carla Bley use quotation for trans-contextualization (12). Coleman, like many jazz musicians, quotes themes and melodies that he did not compose.

For example, in the past several years when performing his composition “Turnaround”, a blues in C, Coleman often quotes “If I Loved You” from the musical Carousel. A parody of a play, Carousel premiered on Broadway in 1945 and a film version was released in 1956.[i] One may hear Coleman’s quote at the 50-second mark on the live version of “Turnaround” from the 2005 CD release Sound Grammar. More will be expressed about this later.

The second type of parody, reformation, is a respectful ethos that may be likened to the Renaissance and Baroque practice of imitation (65). This orientation is expressed by this author as a yardstick for the documented scope of historical reference not as cultural distinction. Parodic reformation in music is much more complicated than quotation because it is a technique that reconfigures or transforms a previous existing work. Contemporary parody uses a “target” text – another work – which in itself has another form of coded discourse that exists from the time period of it’s original creation (16). In this way, “Parody is repetition with critical distance” (20).

Coleman, like many musicians, composed alternative melodies, a ‘contrafact’, over standard chord progressions (Spellman 92). Although the use of a ‘contrafact’ is a deliberate form of imitation, modern parody remodels familiar forms in order to say something serious with greater impact (Hutcheon 65). Most importantly, Hutcheon notes, “musical parody is an acknowledged reworking of pre-existent material, but with no ridiculing intent” (65). Additionally, in parody, the repetition has a difference in that there is a distance between the model and the parody that is created by a stylistic dichotomy (67). There must be a sense of difference and Coleman always provides that. The differential rubric involves his personal sound, how he interacts with the rhythm section, his vocabulary, sonic effects, and naturally, the types of compositions he performs.

Early on Coleman used previously existing forms found in the bebop genre and substituted his own method to convert the music into something new. Modern parody is a dialogue with the forms of the past, a dialogue that re-circulates rather than immortalizes. In this way, parody expresses a genealogical function.

In a New York Times interview, Coleman states, “It (bebop) was the most advanced collective way of playing a melody and at the same time improvising on it.”[ii] Coleman goes on to state, “I was drawn to the way Charlie Parker phrased his ideas…(because) it sounded more like he was composing, and I really loved that. Then, when I found out that the minor seventh and the major seventh was the structure of bebop music — well, it’s a sequence. It’s the art of sequences. I kind of felt, like, I got to get out of this.”[iii] About Coleman, Jon Pareles wrote, “Steeped in bebop, he knows the rules but dances around them, treating tonal harmony the way M. C. Escher treats perspective.”[iv]

One way that Coleman early on transformed bebop into his own language was converting the common use of the bridge in an AABA form. On his first album, Something Else!!! – The Music of Ornette Coleman, recorded in early 1958, two compositions, “Chippie” and “Alpha”, use the 32 bar form and harmonic structure of rhythm changes. However, on these Coleman pieces, the bridge functions as an improvised interlude. Pianist Ethan Iverson notes, “This was common practice already: famous examples include Sonny Rollins’s “Oleo” and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Wee.”[v] Despite the fact that this was demonstrated by leading jazz artists, the crucial revelation Coleman tells Iverson is that improvising on “the bridge of rhythm changes was how he first knew how to leave the home key.” [vi] From this, Iverson postulates, the “bridge of rhythm changes = start of free jazz.” [vii]

Coleman parodied mainstream popular music on his composition “School Work”. Writer James Isaacs identifies in the liner notes to the CD re-issue, this composition touches on the first two bars in the bridge of ‘The Jamies’ 1958 doo-wop/rock ‘n’ roll hit “Summertime, Summertime” (15). Coleman’s “School Work” was recorded in September 1971 and in 1972 Coleman used this theme in his orchestral work Skies Of America (which is discussed further below) and re-titled it “The Good Life” (4).

Coleman demonstrates how he transformed the presentation of solos on Live at the Hillcrest Club, which was recorded in October 1958. Peter Niklas Wilson notes that on this record the piece, “Crossroads” features a unique development in jazz (132). Each soloist is unaccompanied by the piano, bass and drum rhythm section. After the fragmented theme is stated, a capella solos are performed by Coleman, trumpeter Don Cherry, and pianist Paul Bley. After all the solos, the theme is restated twice to conclude the composition, which clocks in at less than two minutes. Presenting three consecutive unaccompanied solos demonstrates Coleman’s power to convert established norms in the bebop genre. A few years later, Coleman reworked this piece. Iverson notes, “A second theme was added to “Crossroads” and became “The Circle with the Hole in the Middle” on The Art of The Improvisers.”[viii] One may observe that the title to the latter piece may allude to the circular form, AABA, with the uncomposed/improvised B section being the “hole”. Omitting the accompaniment on solos influenced other musicians including saxophonist John Coltrane who states, “there probably will be some songs in the future that we’re going to play, just as Ornette does, with no accompaniment from the piano at all – except on maybe the melody, but as far as the solo, no accompaniment” (Porter 203).

Parody can produce an important sociological impact in the relationship between “high” and “low” art. These ‘judgment of taste’ distinctions, explicit or implicit in a society, produce hegemonic attitudes that foster cultural barriers. Anthropologists Raymond Scupin and Christopher R. DeCorse state, “In some societies, especially complex societies with many different groups, an ideology may produce cultural hegemony, the ideological control by one dominant group over values, beliefs, and norms” (254).

Social theorist Pierre Bourdieu dissects distinguishing characteristics in class hierarchies with respect to the study of culture in Distinction – A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Bourdieu’s scientific observations address characteristics of cultural practices as different types of “concert-going” venues and preferences in music (1). A paradox develops when “high” and “low” art aesthetics are combined because sociological, class, gender, and economic barriers are inverted, subverted or reappropriated. Hutcheon argues for calling complex forms of “trans-contextualization” and inversion by the name of parody (15). Using parody, Coleman powerfully combines high and low art aesthetics. In the 1960’s some of Coleman’s compositions reflected traditional European classical models. In 1962, he composed and recorded a string quartet, “Dedication to Poets and Writers” and then in 1965, he composed and recorded a wind quintet, “Sounds and Forms” (Wilson 33, 47). Furthermore, Wilson notes that Coleman’s 1966 European debut with bass virtuoso David Izenson and drummer Charles Moffett were “marked by a unique balance of innovation and tradition” (49). Izenson was a master of contemporary classical bowing techniques and Moffett developed from traditional jazz and bebop. Some of the breakthroughs with this ensemble include having the bass be a “full-fledged melodic instrument”, theme-less improvisations, and Coleman’s extensive use of the violin for “pure sound invention” (49).

A new hybrid form is developed when “high” and “low” art are combined. Hutcheon notes, “the contemporary novel that parodic ally incorporates high and low art forms is another variant of what Russian philosopher, literary critic, semiotician and scholar Mikhail Bakhtin valued in fiction, “the dialogic or polyphonic” (81). In addition to the examples stated above, Coleman juxtaposes “high” and “low” art in his orchestral piece Skies Of America, where a full orchestra is combined with a jazz quartet. This piece increased Coleman’s stature in the music world. Coleman’s music asks the orchestra to improvise by asking the conductor to participate with the improvising quartet. The combination of these techniques, pre-composed and spontaneously composed material, inverts the musicological and social conventions of western classical music.

Coleman’s inspiration may illuminate parodic reworkings and other theoretical approaches.

Coleman has said that Skies Of America was inspired to describe the beauty of America “and not have it be racial or (based on) any territory” (Litweiler 143). He added ‘the sky has no territory; only the land has territory” (143). Coleman has also spoken about another inspiration for the same work. This came from his participation is sacred rites held on a Crow Indian reservation in Montana (143). Apparently he got a feeling from the sky that “everything that has ever happened in America, from way before the Europeans arrived, is still intact as far as the sky is concerned” (143). In this respect, pre and post-colonial approaches may play into the perspective of this orchestral work that combines with a jazz quartet.

Sometimes Coleman revises traditional references.

Longtime drummer with Coleman, Billy Higgins mentioned that Coleman “started writing things that were 11 bars, or 6.” (Wilson 36). Wilson notes, “the shape of the phrases alone determines the form and meter” (79). Wilson observes that “Bird Food” is harmonically close to George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm”. Additionally, Coleman’s tune is in B-flat, the standard key for “rhythm changes” and he uses the same AABA form. However, in “Bird Food”, Coleman’s A-section theme is 9 ½ bars (or nine 4/4 measures and one 2/4 measure). For clarity, Wilson offers a transcription of the A-section theme (78). The B-section begins at the 25.24-second mark and extends to the 31.38-second mark. In the B-section this author counts 38-quarter notes as performed by the bassist Charlie Haden. This is the same number of beats as the A-sections 9 ½ bar theme. Continuing forward, Coleman begins the A-section theme. Trumpeter Don Cherry joins Coleman on the third note of this last A-section. Thus each section of the AABA form is symmetrically balanced in a traditional fashion.

Another Coleman ballad in AABA form is “Just For You”. However, the A-section is only seven bars long (132). Wilson states that this music “should convince even entrenched opponents of free jazz that Coleman’s musical edifice rests firmly on a traditional foundation” (132). Furthermore, Wilson observes, “As the title suggests, “The Legend of Bebop” also harkens back to tradition” (132). We hear this in the rhythmic and melodic language. Traditional features appear on the theme of “R.P.D.D”. Wilson notes that this is a 32 bar AABA song form (124). He goes on to note that Coleman “draws on simple melodic sequences and reminiscences from his rhythm and blues past” and that “references to tradition . . . become quite obvious here” (124).

Using parodic reference, Coleman has transformed other types of music.

Writer Howard Mandel states that the 1995 CD Tone Dialing “draws on energies associated with hip-hop, Central American music, rock, musique concrete and blues” (Mandel 181). Mandel asserts, “It (Tone Dialing) aspires to be a truly universal tract, demonstrating by all it subsumes how far-flung traditions manifest a single inherently human culture” (181). Also on Tone Dialing, Coleman covers Bach and revisits his own compositions (181).

Some of Coleman’s compositions refer to parodic genres such as science fiction and soap operas.

Dating back to at least Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – Or, the Modern Prometheus, science fiction, itself a parodic genre, explores how man tests the boundaries of ethics and scientific intellect. Interestingly, Frankenstein’s subtitle explicitly references its parody of the Greek myth. As a genre, science fiction explores human anxieties that develop from the threats of new technologies and “futuristic” scientific hypothesis such as controlling life and death, space and time travel, alien life, and manipulating the body genetically or through cloning. Although Frankenstein is one exception, works of science fiction do not strongly factor into the Western canon of literature as being the most important and influential in shaping Western culture. But who decides what is in the canon?

Bourdieu writes that each class has their own aesthetic, which is in fact an ethos (4-5). As their appreciation has an ethical basis, “popular taste applies the schemes of the ethos” to decide which works of art are ‘legitimate’ (5). Bourdieu states, “one can never entirely escape from the hierarchy of legitimacies” (88). Perhaps if one cannot escape, one may transgress. Bourdieu notes that detective stories, science fiction and comic strip cartoons have meaning based on the “system of objects in which they are placed”. So, when Garry Trudeau’s “Doonesbury” is placed in the editorial section, instead of the back pages of the entertainment section along with “Peanuts”, “Blondie” and “Family Circus”, the strip gains cultural prestige. Bourdieu notes:

“Science fiction or strip cartoons may be entirely prestigious cultural assets or be reduced to their ordinary value, depending on whether they are associated with avant-garde literature or music – in which case they appear as manifestations of daring and freedom –or combine to form a constellation typical of middle-brow taste – when they appear as what they are, simple substitutes for legitimate assets (88).”

The use of parody is one way for a ‘low-brow’ genre to gain cultural capital and respect. Coleman exerts this power with respect to science fiction. In 1971, he released Science Fiction, a critically acclaimed album. Although many of the songs sound like they come from a parallel universe, utilizing alien sounds and studio sound effects, Coleman references many aspects of his history including personnel, instrumentation, musical forms and improvisation. Additionally, Coleman’s science fiction compositions including “Cloning” and “Latin Genetics”, express a relationship with science similar to Shelly’s account of a man’s manipulation of life and the body.

Another type of parody that Coleman pursues is the television soap opera. TV soaps are a form of parody as their genealogy traces back to radio and periodical based serialized fiction.

In January 1977, Coleman and bassist Charlie Haden made a duo record called Soapsuds, Soapsuds, that included his composition “Soapsuds” and the theme song “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman”, from the Norman Lear produced television show; itself a parody of afternoon “soap operas” and the commercials that sponsored the programs. Louise Lasser starred as the pigtailed and depressed housewife who appeared to be oblivious to the causes of anxiety in her life. The writing fostered compassion and empathy not ridicule or derision for the protagonist. Correspondingly, the overproduced sentimental and florid theme music with crescendo string swells is a parody of standard daytime serial schmaltz. Coleman and Haden play the theme straight and poignantly express the music before going into double time for the improvisations. The exuberant improvisations are examples of “parody’s power to revitalize” (Hutcheon 115).

In order for parody to work, the audience must be able to ascertain those aspects that refer to existing work, versus those that reflect parodic comment or reformation. As such, parody has a relationship between encoder and decoder (27). Hutcheon notes, “any discursive situation, not just a parodic one, includes an enunciating addresser and encoder as well as a receiver of the text” (85). She states that the description of the function of parody is predicated on the recognition and interpretation of parody (84).

Occasionally Coleman titles songs with acronyms. Two of his compositions are believed to be acronyms of books by Sigmund Freud.[ix] “T. & T.” is thought to be “Totem and Taboo” and “C. & D.” is “Civilization and It’s Discontents”. Perhaps this is Coleman’s desire to parody the discoverer of the unconscious. In essence, the discoverer of pre-conscious improvisation jousts with the discoverer of the unconscious.

Parodic music employs both simple and complex codes. For example, the language of Bebop and Charlie Parker’s music is highly stylized with it’s own array of rhythms, patterns, enclosure gestures, and articulations that Coleman was well versed in. Ekkehard Jost states, “By the end of the Fifties, many of Coleman’s themes are still based on patterns from bebop and its derivatives.” Coleman’s compositions “Chippie”, “The Disguise” and “Alpha” employ intervallic structures and sentence lengths which adhere, for the most part, to traditional four bar units similar to those compositions by Charlie Parker (56). Earlier, we discussed the form of “Bird Food”. In this composition, Coleman may be channeling Charlie Parker’s language. Charlie Parker’s moniker was “Bird” and earlier statements by Coleman in this essay demonstrate the influence Parker had on Coleman. Perhaps Coleman’s title implicitly acknowledges Parker’s language as “food for thought” or “food for creativity” for his own composition.

The difficulty in understanding Coleman’s music may come from the fact that listeners often don’t know how to decode it. After a few decades studying his music, this author has learned to decode songs by first focusing on the form Ornette uses. Is the song a folk song? A blues? An AABA form with rhythm changes? By recognizing the form, one can then begin the process of decoding the message, based on how the form is being treated by the composer. For example, here’s how I decode Coleman’s quotation of the song “If I Loved You” in his composition “Turnaround”. The form of “Turnaround” is a 12 bar blues, which is one of the most authentic American musical forms. The song “If I Loved You” from the musical Carousel, was composed post WWII, in the beginning of the Cold war era, when American culture began to find the notion of sincerity suspect. The song is sung by the female lead and she sings it to the man she has feelings for, but she protects herself as she chooses to not be sincerely frank in expressing her feelings. Coleman’s parodic quotation of “If I Loved You” within the 12 bar blues song “Turnaround” sheds light on his intention. Instead of Coleman verbally announcing to the audience “I Love You” (which he sometimes does), he performs this beautiful melody, which surreptitiously gets the sentiment across in a way such that its sincerity cannot be doubted. This is an example of decoding a quotation, the first, simple form of parody.

An example of decoding the second, more complex type of parody, reformation, can be seen in Skies of America. The form of the piece is an orchestral work, which evokes the notion of “high” art. By the very nature of the piece you have to go to a concert hall that is designed to present an orchestra, with a stage large enough to also accommodate a jazz quartet, rather than a nightclub, bar or theater. However, the music is inspired by non-European events and culture. Despite this, the European influence has affected those events and people, and the musical experience of Skies of America reflects this dichotomy by combining the experiences of an Afro-logical jazz quartet [x], with the simultaneous sound architecture and sociology of an orchestra. Thus, the decoding of parody enables us to understand the composer’s deeper embedded messages, which have vast cultural significance.

Hutcheon states that the ideological status of parody cannot be permanently fixed and defined (99). Additionally, theorist Bill Nichols states, “Parody, or ‘reflexive art’, like this where signifiers refer to other previous signifiers in a formal game of inter-textuality has no necessary relationship to radical innovation at either a formal, avant-garde level or a political, vanguard level.” (Hutcheon 99; Nichols 65). Parody, like allusion and quotation, may act as a ‘badge of learning” for both encoders and decoders. Additionally, as parody works towards maintaining cultural continuity, it makes change possible.

Ornette Coleman has employed parody throughout his career to both highlight cultural continuity through quotation, as well as break through musical and cultural boundaries using parodic reformation and recontextualization. This fosters regional economic and socio-political transformation while simultaneously transcending global distribution boundaries. Coleman’s work, sometimes called “Free Jazz” established a musical ideology that has worldwide practitioners. Coleman influenced many musicians including Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett and Pat Metheny. These artists and others, produced recordings and concerts utilizing Coleman’s perspectives. Furthermore, productions of hybrid forms like Skies of America set precedents that help to break down hegemonic barriers in order to transcend Eurocentric boundaries in the Western European classical tradition. Throughout his career Coleman has used both types of parody in his music and thus his work is part of a genealogical lineage that reworks and revitalizes the past. Knowledge and power interact in historical and social contexts to produce new musical paradigms for interpreting the world. Paradigms shift over time. Parody is an important way that paradigms are made to shift. The critical distance created through the use of parody may produce new paradigms for interpreting the world.

End Notes

[i] It is interesting to note that Carousel was adapted from Ferenc Molnár’s 1909 play Liliom, transplanting its Budapest setting to the Maine coastline. An English translation of Liliom was presented in New York City in 1921 and the play was a success, running 300 performances (Hischak 30). Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II saw a 1940 revival, with Burgess Meredith and Ingrid Bergman, and then bought the rights and converted it into a musical (Nolan 153). Carousel, a parody of a play, premiered on Broadway in 1945 and a film version was released in 1956.

[ii] Ratliff, Ben. “Listening With Ornette Coleman – Seeking the Mystical Inside the Music.” New York Times. 22 September 2006. Nytimes.com. 15 April 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/22/arts/music/22cole.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all>

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Pareles, Jon. “Ornette Coleman Gets the Treatment.” New York Times. 6 July 1997. Nytimes.com. 15 April 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/1997/07/06/magazine/ornette-coleman-gets-the-treatment.html>

[v] Iverson, Ethan. “This Is Our Mystic.” Do The Math Weblog. 19 September 2010. 15 April 2012. <http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/this-is-our-mystic.html>

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] This information was learned by this author too long ago to recall the citation.

[x] This is a reference to George Lewis’ term used in Black Music Journal.

Bibliography

Baraka, Amiri [Leroi Jones]. Black Music. New York: Da Capo Press, 1968. Print.

Berliner, Paul. Thinking in Jazz- The Infinite Art of Improvisation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. Print.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984. Print.

Cole, Bill. John Coltrane. New York: Da Capo Press, 1993. Print.

Coleman, Ornette. 26 Compositions. New York: MJQ Music, 1968. Print.

Foucault, Michel. Power. Ed. James D. Faubion. New York: The New Press, 1994.

———. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Trans. Colin Gordon et al. New York: Pantheon, 1980. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. Civilization And Its Discontents. Trans. James Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961. Print.

———. Totem and Taboo. Trans. James Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton, 1950. Print.

Hischak, Thomas S. The Rodgers and Hammerstein Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. Print.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000. Print.

Isaacs, James. “Liner notes.” Science Fiction. Columbia/Legacy, 2000. CD.

Iverson, Ethan. “This Is Our Mystic.” Do The Math Weblog. 19 September 2010. 15 April 2012. <http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/this-is-our-mystic.html>

Jost, Ekkehard. Free Jazz. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975. Print.

Kofsky, Frank. Black Nationalism and the Revolution in Music. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970. Print.

Lewis, George. “Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives”. Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 16, no. 1 (1996). Print.

Litweiler, John. Ornette Coleman – A Harmolodic Life. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992. Print.

Nolan, Frederick. The Sound of Their Music: The Story of Rodgers and Hammerstein. Cambridge, Mass.: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2002. Print.

Pareles, Jon. “Ornette Coleman Gets the Treatment.” New York Times. 6 July 1997. Nytimes.com. 15 April 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/1997/07/06/magazine/ornette-coleman-gets-the-treatment.html>

Porter, Lewis. John Coltrane – His Life and Music. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1998. Print.

Ratliff, Ben. “Listening With Ornette Coleman – Seeking the Mystical Inside the Music.” New York Times. 22 September 2006. Nytimes.com. 15 April 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/22/arts/music/22cole.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all>

Scupin, Raymond and Christopher R. DeCorse. Anthropology: A Global Perspective (6th Edition).Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2008. Print.

Such, David. Avant-Garde Jazz Musicians – Performing ‘Out There’. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993. Print.

Thomas, J.C. Chasin’ the Trane – The Music and Mystique of John Coltrane. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975. Print.

Wilmer, Valerie. As Serious as Your Life – The Story of the New Jazz. New York: Serpent’s Tail, 1992. Print.

DISCOGRAPHY

Coleman, Ornette. “Alpha.” Something Else!!! – The Music of Ornette Coleman. Contemporary, 1988. CD.

———. Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “Bird Food.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “C.&D.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “Chippie.” Something Else!!! – The Music of Ornette Coleman. Contemporary, 1988. CD.

———. “The Circle With A Hole In The Middle.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “Crossroads.” Complete Live at the Hillcrest Club. Gambit Records, CD.

———. “The Disguise.” Something Else!!! – The Music of Ornette Coleman. Contemporary, 1988. CD.

———. “The Good Life.” Skies Of America. Columbia/Legacy, 2000. CD.

———. “Just For You.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “The Legend of Bebop.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.” Soap Suds, Soap Suds. Polygram, 1978.

———. “R.P.D.D.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. “School Work.” Science Fiction. Columbia/Legacy, 2000. CD.

———. Science Fiction. Columbia/Legacy, 2000. CD.

———. “Skies Of America.” Skies Of America. Columbia/Legacy, 2000. CD.

———. “Soap Suds.” Soap Suds, Soap Suds. Polygram, 1978. Record.

———. “T.&T.” Beauty Is A Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings. Rhino, 1993. CD.

———. Tone Dialing. Polygram, 1995. CD.

———. “Turnaround.” Sound Grammar. Sound Grammar, 2006. CD.

################################################################################################

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles