Dreams may be the source of songs. Personally, I’ve had some of those. Games may be another source for songs. Kids do this all the time. Practically every game I played as a kid had a song that went along with the activity. Even as an adult, I make up songs almost everyday while I’m playing with my dog.

This is the third and last paper, with this heading, that will be published here. In earlier blog entries you’ll find my first two papers and some background info. In this essay we will investigate the use of narrative songs, game songs, cross cultural collaborations, the celebration of community relationships, contemporary intertribal encounters

Another subject we will look at in this essay is Native American throat singing. With throat singing, two or more pitches may be produced simultaneously. The sound is hauntingly beautiful. I think the first time I ever heard throat singing in person was in the 1990’s by the bassist Peter Kowald. Furthermore some saxophonists including John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Dewey Redman and Evan Parker along with a few contemporary trumpeters including my friend and musical cohort Peter Evans, seem to simulate this through their own means. Don’t get me wrong. They’re not throat singing but they do produce multiple pitches simultaneously. Although I don’t want to assume I know how each of them produces “those” sounds, the sounds are exciting to be around. You gotta hear it in person!

Understanding and Listening to Native American Music

“Human wellbeing involves far more than simple adjustment to a given environment, natural or cultural; it involves endless experimentation in how the given world can be lived decisively, on one’s own terms” (xii).

~ Dr. Michael Jackson, Existential Anthropology: Events, Exigencies and Effects

In order to understand and listen to Native American music, it is essential to understand human behavior through the study of people because the enculturated “mythical ideas of racial essences (which) are deeply embedded within the folk culture of U.S. society” have to be recognized so that romanticized stereotypes may be challenged (Scupin and DeCorse 604). Native Americans defy these stereotypes and live on their own terms through the preservation and renewal of traditional indigenous knowledge [TIK]. The preservation and renewal of TIK will be observed in a variety of themes including the development of contemporary identity and the preservation of cultural identity, how music is preserved through TIK, the expression of sound as an encounter with one’s environment, song as a mirror of nature, the role of music in oral literature, cross-cultural collaborations with issues of intellectual property rights and subsequent changes in traditional practices, the socio-cultural benefits contrasted with commercial threats of the erosion of cultural identity and community, and how the celebration of community relationships preserves and renews TIK through periodic ceremonies.

In Native American Music in Eastern North America, ethnomusicologist Beverley Diamond explores how to better understand human behavior in several diverse Native American music making communities. In chapters 2-5, Diamond explores historical and contemporary encounters. Diamond is adept at deconstructing the western Eurocentric perspective of indigenous people to show that indigenous modernity is interwoven with the preservation of primordial aspects of TIK. The Eurocentric propensity to reduce diverse non-European based musical expressions of musical information to “standard notation” as a way to represent “expression” is ironically symbolic of narrow cultural understanding. Diamond goes to great lengths to represent indigenous musical expression on its own terms. In addition, as the history of subjugation and forced assimilation by the Bureau of Indian Affairs is an ongoing challenge to TIK and Native American expressions of modernity, the preservation and renewal of TIK is, as we shall see, also ongoing.

When Native North Americans perform narrative songs with drum accompaniment, TIK is preserved. Depending on the communities, the songs may be called pisiit or ajaja songs. These songs constitute a historical record and typically express very strong emotions such as extreme loneliness, shyness, displacement, or a hunter’s failure to provide. However, other narrative topics may be about happy familial relationships or sexual exploits (Diamond 43). The traditional use of music may be private, or related to the environment, or designed to balance internal and external social relationships (62). TIK has traditionally been retained through participation with one’s environment. Once colonization and the influence of missionaries began, the men who traveled to remote areas to hunt and fish primarily retained and traded TIK. In these remote environments, hunters shared traditional stories and their dreams, which were a source of prophecy, wisdom and songs. For Innu hunters, dreams offered knowledge, contact with the spirit world and means to acquiring personal power. Diamond states “dreams are the only source of songs…” (64). A song revealed in a dream is called nikamun. For personal discovery and enrichment, as well as in performance, a hunter uses a drum as a channel to the dream world. The drum functions like a window into the world of the dream. Hunters consider nikamuna a private spiritual genre and hunters are not prone to sharing these for use outside their communities. Songs that express relationship with one’s environment may be an expression of “traditional ecological knowledge” [TEK]. These songs express man’s respectful relationship with Mother Earth. Additionally, the songs may be about rituals of renewal such as Green Corn Ceremonies, which gives thanks for the harvest and is a means of purification (68).

Numerous examples of Native American modernity demonstrate, either explicitly or implicitly, that traditional and modern knowledge are not dichotomous and separate realms (154). Music promotes this interweaving and is expressed, as we shall see, in a variety of vocal games and social interactions. Just as TIK is rooted in ways of observing and participating in one’s natural and social environments, TIK informs and fosters contemporary expression.

Game songs were developed by women and children and are associated with indoor spaces. Due to living in close proximity, these games are used to bring joy and laughter to those environments (46). The musical games transform the nature of the space. Anthropologists Raymond Scupin and Christopher R. DeCorse note that language “is the most important means of expressing and transmitting symbols and culture from one person to another” (Scupin and DeCorse 321). Game songs are used in string games like “cat’s cradle”, for juggling, hide and seek, as a form of linguistic playfulness, and during regional or international competitive games. With respect to linguistic games, singers may alternate singing the notes of the melody or text syllables as is demonstrated on track 5, Qiarvaaq, of the CD accompanying Native American Music in Eastern North America. Here, Betty Peryuaq And Hattie Atutuva perform complex vocal sounds with multiple layers and textures. Music facilitates the renewal of language through vocal games and as these vocal games promote cultural identity we shall also see that they revitalize powerful traditional cultures in both regional and international competitions.

Women’s vocal games, commonly referred to as “throat singing”, receive a great deal of attention regionally and internationally. Throat singing is a contemporary expression of sound as an encounter with one’s environment. Throat singing demonstrates unique timbres and vocal gestures. Qualities of a good throat singer include endurance, talent to create a range of sounds, and power to increase the tempo (Diamond 52). Throat singers strive to imitate sounds of their environment such as the wind, a river, seagulls, a mosquito, a puppy, or the polishing of sled runners. On track 6, Qimmruluapik, from the aforementioned CD, we hear a Nunavik game that employs vocables and throat singing from Puvirnituq elders Lucy Amarualik and Alavie Tullaugaq who are among the earliest recorded practitioners of this expression (49). The rhythm of the breathing is sonically emphasized as their voices imitate sounds of nature with a broad range of frequencies. Musical expression connects them to their lands, customs and ancestors. These songs touch on several concepts, some mentioned earlier and some later in this essay, including environmental influence and cooperation, regional singing styles, the role of music in oral literature, song as a mirror of nature, variation from exact repetition, and group/self-identification through the transmission of cultural legends. The far-reaching socio-cultural benefits include increasing local participation in community activities, revitalizing local culture and traditions, strengthening community identity and pride, and developing social capital.

Karin and Kathy Kettler, the Canadian throat-singing sisters who together are known as Nukariik, carry on the traditions of the elders from their mothers’ village in Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik, which is located in northern Quebec.

More recently, Native North American throat singers have been collaborating with singers from around the world. Cross-cultural collaboration is a recent contemporary trend where Native North American throat singers meet with Tuvan and Danish throat singers. However, concerns have been expressed regarding issues of intellectual property rights and changes in traditional practices. Members of some communities feel that cultural identity is lost when powerful expressions, specific to communities, are diluted to appeal to a greater commercial audience. For instance, throat singing initially developed through close physical proximity between singers, utilizing a reflective surface or a parka hood to enhance the “feeling” of the rhythms and resonance of the sounds. Subsequently, with increased public interest, they sing to a larger audience and in order to demonstrate their singing in new sonic environments, singers must change their approach, methodology and innate motivation by using microphones in an amplified arena where their concentration is on the audience and not themselves. Thus the process of encounter between the singers and the audience changes both within and among communities and cultures. However, because the sounds of specific localities, and the sounds of song traditions from neighbors or foreigners inform one’s awareness, experience and knowledge, these expressions of modernity also encourage comparison between different ways of enjoying, learning, and using music. Just as some encounters celebrate cross- cultural exchanges, other encounters celebrate community relationships.

The celebration of community relationships preserves and renews TIK through periodic ceremonies. The Haudenosaunee music culture has a bi-annual event called “Sing” which may attract 500 people. Funds that are raised contribute to the well being of community members. The event begins with an elder who acknowledges TEK; elements of the environment such as plants, fruits, water, food, etc. Although he doesn’t sing, the tone of his voice employs melodic cadences thus imparting a song like quality. After this address, groups of singers take turns performing eskanye, new Women’s Shuffle dances (97). These contemporary compositions also utilize a water drum and cow-horn rattles for percussion. There is no dancing until after dinner, when several types of dances follow, some that are part of the local community and others that are in honor of invited guests from other nations. “Sing” is a celebration of life that affirms the Haudenosaunee’s relationship with their environment and with each other. This is just one of many celebrations that are held throughout the year as Diamond notates eighteen different annual ceremonies (102). These ceremonies help Native Americans preserve and renew traditional indigenous knowledge.

Contemporary intertribal encounters occur when Native people come together from different communities for activities. At intertribal encounters, as TIK informs Native Americans, the knowledge functions to both renew communities and to help a community relate to the larger world on its own terms. Over 170 annual intertribal encounters occur in North America.[1] One example is the Arctic Winter Games (39). The games celebrate sport, social exchange and cultures.[2] For instance, Cherokee ethnomusicologist Marcia Herndon and anthropologist Raymond Fogelson describe the transformative powers of ceremonies that precede an important stickball/Lacrosse game (70). There are two different dances. The function of the first all night dance is to generate a “red” power that brings strength to the players. In the second, a male singer accompanies the women’s dances to conjure a “white” power that serves to weaken the opponents of the other team. Communities are renewed when legends, dance, music and song texts weave traditional and contemporary knowledge to generate power and transform consciousness.

Welcoming songs help a community relate to the larger world through mediation. For example, the Mi´kmaq welcoming songs are traditional songs that are used to mediate encounters. Drum dances have been, and continue to be, traditional celebrations held to welcome home hunters or arriving visitors. Some drum dance songs trace the composer’s travels over specific places. Environmental references in the spoken or sung text evoke memories for listeners who know the territory. Diamond notes that the emotional intensity of the texts is related to the solo drum performance. Specifically, when the drummer plays asynchronously, only occasionally coinciding with the singers, there is greater tension and feelings of isolation felt from the singers. In contemporary experiences, the drumbeats are more frequently synchronized with the song beats. Traditionally, only men played drums. However, women now drum in some communities and children are taught drumming in schools. Subsequently, with traditional gender roles expanded to be more inclusive, the preservation and renewal of TIK benefits communities on a larger scale.

Intertribal and cross-cultural encounters are often recontextualized or fuse traditional song genres with contemporary popular idioms. Historically, intertribal exchange intensified after the forced relocation and movement of eastern Native American cultures. Christian camp meetings functioned as large social gatherings that attracted neighboring Native communities. Intertribal sharing developed at these gatherings. As both traditions used chanting and prayer for ceremonies and rites of passage in treating the sick or burial of the dead, missionaries’ practices were interpreted as similar to the shaman of Native cultures (72). Once trust developed, Native Americans indoctrinated with Christian values were influenced to learn and utilize Eurocentric musical values and practices. Diamond asserts that the missionaries forbade the use of (or destroyed) Native American drums and that the contemporary use of drums is a way to reclaim prior traditions (89-90). Consequently, indigenized Christian and secular musical practices are transformed to create Native expressions of modernity. This is found for instance in Haudenosaunee Oneida hymn groups who have appropriated and assigned indigenous purposes and properties to traditional hymns as a way to recontextualize and respond to the history of colonization and racism.

Another contemporary response related to the forces and consequences of colonization is found in the expression of intertribal powwows. Larger contemporary powwows are competitive events that honor traditional values, kinship and intercommunity ties (121). Although the general sequence of events from one powwow to the next is similar, distinguishing characteristics exist in diverse regions of North America. For instance northern and southern styles differ in tempos, vocal timbre, and dance regalia. The northern style of the Lakota, Dakota, Cree, and Ojibwe is generally characterized as using slower tempos, having more intense timbres and generally being more exuberant than southern or eastern styles (123). Powwow songs use basic standardized forms, fostering intertribal communication and exchange of repertoire (129). Keeping in mind that at any given powwow, participants may reflect dozens of different communities, languages and dialects, the texts of powwow songs are more often than not, composed predominantly of vocables (131). Although Diamond asserts that the tempo of the powwow drum is always ahead of the beat of the song, she doesn’t note why. Perhaps she did not ask the practitioner. As a musician myself, I imagine that the drummer has his own preference and that this preference may be a way to express a variety of things including urgency, power and forward momentum.

Just as international audiences enjoy recordings of powwow music, others enjoy more personal expressions of contemporary Native American music. Personal indigenous expression by Native Americans has been documented for over 100 years. Santu Toney’s 1910 recording documents a personal expression demonstrated in the way that she runs a couple of songs together (80-83). Contemporary Native American recording artists are involved in every genre of popular music. Many sing in English because it is the only practical language for subject matter that shapes a post-colonial discourse and critiques “encounter” (147). Furthermore, the distribution of recorded powwow music has led to the commodification of powwow ceremonies as contemporary Native Americans produce powwows in Argentina, France and Germany (122). UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, sometimes offers tour support for Native American troupes. The benefits include the safeguard, development and promotion of traditional cultures around the world.[3]

The adaptation of sociocultural systems to new environmental conditions is experienced in the revitalization of traditional and contemporary Native American musical expressions. As we have seen, women’s roles in contemporary Native American life are dynamic and important in the study of cultural change. Just as linguistical anthropologists recognize that the structure of language has a sound component, a range of phonemic differences is heard in diverse communities. The representation of music language concepts due to the complexities and subtleties of pitch, timbre, and rhythmic relationships informs the discussion of music as a meaningful exchange in human interaction.

Noam Chomsky’s concept of universal grammar may be inferred when looking at the language of intertribal music. Governmental policies that fostered ethnocide by forcing indigenous people to move from their environments, abandon their traditional language, and replace their ceremonies, cultural philosophies and music has had devastating long-term effects. To this day, the traditional indigenous culture of some ethnic groups is near extinction. Educational programs that foster bilingual curriculums and traditional music practices strengthen cultural identity, retention and community revitalization. Despite the adversity, musicians of Native American heritage have enriched and strongly influenced domestic and international music communities. Contemporary encounters have helped Native American participants revitalize their powerful traditional cultures while living on their own terms in the contemporary world.

New processes of representation may reveal more about the intellectual history of traditional and contemporary Native American music. In retrospect, the multitude of approaches that ethnomusicology has historically embraced has enhanced research skills and our ability to better understand and communicate with diverse cultures. Reviewing the history of cultural perspectives and theoretical underpinnings that have been used by ethnomusicologists causes this author to wonder about other means of understanding that may be contemporaneously emerging. New technologies combined with new perspectives may intertwine to produce a new, more meaningful, musical ethnography. These processes may further enable Native Americans to continue to express their rich cultural traditions on their own terms within the global community.

END NOTES

[1] http://calendar.powwows.com, accessed November 28, 2014.

[2] http://www.arcticwintergames.org/, accessed Dec. 21, 2011.

[3] http://www.powwows.com/2014/05/16/help-send-the-sewam-american-indian-dance-group-to-france/, accessed November 28, 2014

Referenced Works

Arctic Winter Games International Committee. Arctic Winter Games. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. http://www.arcticwintergames.org/, accessed Dec. 21, 2011.

Bohlman, Phillip. “Representation and Cultural Critique.” Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology. Ed. Bruno Nettl and Phillip V. Bohlman. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991. Print.

Browner, Tara, ed. Music of The First Nations – Tradition and Innovation in Native North America. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009. Print.

Diamond, Beverley. Native American Music in Eastern North America: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print.

Jackson, Michael. Existential Anthropology: Events, Exigencies, and Effects (Methodology and History in Anthrolopogy). New York: Berghahn Books, 2005. Print.

Merriam, Alan P. The Anthropology of Music. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964. Print.

Scupin, Raymond and Christopher R. DeCorse. Anthropology: A Global Perspective. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2008. Print.

Stone, Ruth M. Theory for Ethnomusicology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2008.

#########################################################################

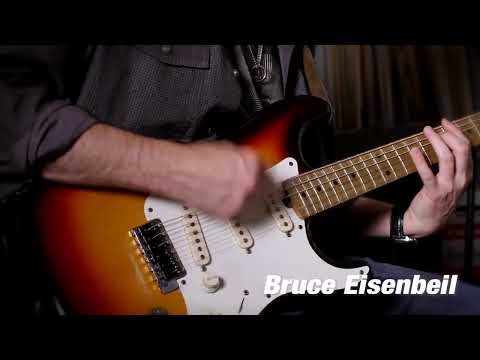

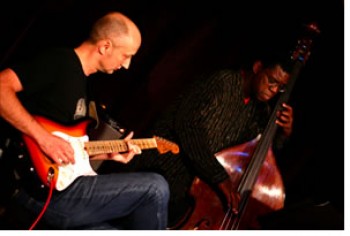

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles