It’s been said, “The word is not the thing” and “The map is not the territory”. With respect to a photograph or for that matter a sound recording, isn’t it just a representation? Basically, as far as music is concerned, is sheet music or a recording of music, for that matter, actually the music that was originally sounded and recorded? With this being the third post in this heading, we are going to dig into the conventional notion that objects correspond to words and images. Through the use of parody we see that artists may create a paradox. Parodic reworkings of previous music may illuminate a rubric of previously hidden perspectives.

Book Review:

A Theory of Parody – The Teachings of

Twentieth Century Art Forms

by Linda Hutcheon

Modern parody is a mode of expression that is flexible, multi-faceted and intertextual. In A Theory of Parody – The Teachings of Twentieth Century Art Forms, Linda Hutcheon observes the use of parody in the works of architects, composers, filmmakers, painters and playwrights. As Hutcheon details the range of intent in contemporary parody, distinguishing characteristics illuminate it’s nature in contrast to allusion, burlesque, pastiche, plagiarism, quotation, satire and travesty. Hutcheon’s book is a reconsideration of both the nature and the function of parody. Hutcheon identifies contemporary parody as a unique theoretical perspective that intersects with invention and critique as a way to deal with the texts and discourses of the past. Parody is a dialogue with the forms of the past, a dialogue that re-circulates rather than immortalizes. In this way, parody expresses it’s genealogical function.

Hutcheon notes that the most commonly cited purpose of parody is “critical ridicule” employing humor and derision (51). However, Hutcheon sees this ethos as an outdated limitation. Historical and modern parody is not always ridicule. Numerous critics have recognized the use of parody as wit devoid of ridicule or burlesque (52). Additionally, Hutcheon notes that parodic texts from T.S. Eliot, James Joyce and Andy Warhol suggest this as well (52). Modern parody has a range from ironic, playful, scornful and ridiculing (6). Although parody is a form of imitation characterized by ironic inversion, it’s focus is not always at the expense of the parodied text (6). Furthermore, satire is not parody. Satire is moral and social in its focus and ameliorative in its intention (16). Modern parody is an ironic playing with multiple conventions; an extended repetition with critical difference (7). In this way, parody may have a productive-creative approach to tradition (7).

Hutcheon mentions that the use of parody in the eighteenth century valorized wit and irony and the function of parody was to be malicious and a denigrating vehicle of satire (11).

Parody in pre-twentieth century writing is found in Cervantes Don Quijote and Byron’s Don Juan, where the women chase after the man and Hugh Selwyn Mauberley is a parody of Dante’s Commedia. In the twentieth century, parody can play the above role but Hutcheon notes that modern parody has a formal, ideological and pragmatic complexity (xvii). Hutcheon argues for calling complex forms of “trans-contextualization” and inversion by the name of parody (15). Contemporary parody uses a “target” text – another work – which in itself has another form of coded discourse that exists from the time period of it’s original creation (16).

As Hutcheon defines the historical use of the term parody we learn that attacks against parody include that it is an enemy of creative genius and vital originality (4). Attacks of this sort expose the continuing strength of a Romantic aesthetic that values a different orientation towards genius, originality, and individuality (4). These attacks may be more deeply rooted in the enlightenment era philosophy which itself is under greater scrutiny. By examining the genealogy of parody, we see the importance of the process. The process is culturally important to the development of significant new works.

One may observe this in Joyce’s Ulysses as a parody of Homer’s Odyssey. Hutcheon succinctly notes, “parody is repetition with critical distance” (20).

Coming out of an era that tried so hard to define a literary canon, it is understandable that Hutcheon feels that modern work is haunted by the tyrannical weight of cultural memory (5). The struggle to become an individual, free from the tyrant, is expressed through subversion and transgression. One may slay the Nietzschean dragon that demands “Thou Shalt” through incorporation and inversion of perceived cultural tyrannies.

With the renewed interest in textual appropriation and influence, parody is a model for the process of transfer and reorganization of the past. This contemporary expression is fostered by artists who recognize that change entails continuity (4). In the twentieth century parody is observed in Ezra Pound’s Winter is icummen in, and Eliot’s use of allusion and parody in The Wasteland (2). Other writers Hutcheon mentions include John Fowles, Italo Calvino, and Max Beerbohm.

A remarkable range of intent in modern parody may be observed by looking at works in diverse genres.

The caption below the image is translated as, “This Is Not A Pipe”. However, this painting by René Magritte’s is actually titled, “The Treachery of Images”.

Painters such as Max Ernst with his work Pieta and Rene Magritte in his work This Is Not a Pipe, explore transgressions of general conventions of representation and reference in art (3). Other genres include playwright Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, filmmakers Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, Brian de Palma’s Blowout and Dressed to Kill and Woody Allen’s Play It Again Sam and Zelig.

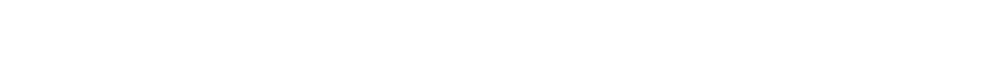

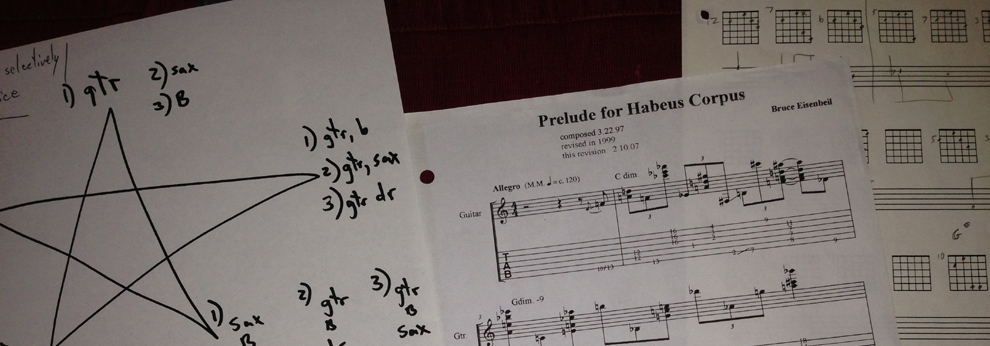

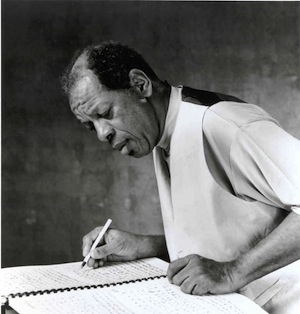

Composers express modern parody as well. Hutcheon expresses, “a major way that music can comment upon itself from within …is through parodic reworkings of previous music (3). Double-voiced parodic forms play on the tensions created by the employment of historical awareness (4). Hutcheon notes that Bertolt Brecht’s Three Penny Opera is an updating of The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay (1728), which is a parody of Handel (23).

Additionally, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Hymnen alters the melodies of many different national anthems and the third movement of George Rochberg’s third string quartet evokes the style of Beethoven’s late quartets.

Hutcheon notes that jazz artists such as Carla Bley use quotation for trans-contextualization (12). Furthermore this author would include works by Ornette Coleman, Frank Zappa, and John Zorn.

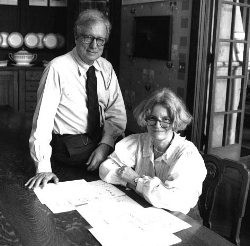

Hutcheon mentions Post-Modern architecture as being a form of parody as the work is a dialog with the past.

Hutcheon mentions Robert Venturi, Paolo Portoghesi and Charles Moore (11). On a personal note, after meeting Venturi in 1988, his book Learning From Las Vegas, inspired this author to compose music in new ways.

Although parody is a form of auto-referentiality with ideological implications, the ideological status of parody cannot be permanently fixed and defined (99). Hutcheon quotes theoretician Bill Nichols who states, “Parody, or ‘reflexive art’, like this where signifiers refer to other previous signifiers in a formal game of inter-textuality has no necessary relationship to radical innovation at either a formal, avant-garde level or a political, vanguard level.” (99).

Although the use of a ‘contrafact’ is a deliberate form of imitation, modern parody is developed by remodeling familiar forms in order to say something serious with greater impact (65). Hutcheon notes that in music, parody has two distinct meanings. The first meaning is a respectful ethos that may be likened to the Renaissance and Classical practice of imitation (65). This orientation is used as a yardstick for the scope of historical reference, not as cultural distinction. Most importantly, Hutcheon notes, “musical parody is an acknowledged reworking of pre-existent material, but with no ridiculing intent” (65). Additionally, in parody, the repetition has a difference in that there is a distance between the model and the parody that is created by a stylistic dichotomy (67). There must be a sense of difference. Furthermore, this sense of difference is even more evident in the second, non-generic meaning of musical parody where the composition has humorous intent (67). This type of parody in music may explore a variety of limited phenomenon including the quotation of isolated themes, rhythms, chords, etc. This is a more traditional type of parody. This type is not a global reworking that fuses old and new elements. The first type is potentially more fruitful as it allows the artist to use parody to transform and remodel existing musical forms without any specifying of ridiculing intent (67).

Hutcheon notes the central paradox of parody is that transgression is always authorized (26). The textual and pragmatic nature of parody simultaneously implies authority and transgression (69). The language of parody subverts the traditional mention/usage distinction as it refers both to itself and that which it designates. Hutcheon notes, “the contemporary novel that parodically incorporates high and low art forms is another variant of what Bakhtin valued in fiction, the dialogic or polyphonic” (81).

A theoretical perspective, be it cognitive, Marxist or literary such as parody, has a relationship between encoder and decoder. Hutcheon notes, “Parody depends upon recognition and therefore it inevitably raises issues of both the competence of the decoder and the skill of the encoder (xvi).” Parody, like allusion and quotation, may act as a ‘badge of learning’ for both encoders and decoders. The pointing to the literariness of the text may be achieved by using parody (31). An internal self-reflecting mirror (mise-en-abyme) will signal this dual ontological status to the reader. (31). As Parody works towards maintaining cultural continuity, it makes possible change. As parody reflects on a historical text, the use of parody places the historical text into situation with the contemporary era. In this way, the text’s “situation in the world” involves the sharing of codes in an act of communication between encoder and decoder (108).

Hutcheon identifies the essential qualities of parody by separating it’s unique characteristics from other genres that use irony as a rhetorical strategy. By exploring the difference between the parodied text and the present we are able to confront the past through a contemporary lens. Hutcheon’s inquiry is the relation of theory to artistic practice. Hutcheon makes the point that theory should be derived from and not imposed upon art (xi). As parody changes with the culture it is essential to recognize the relationship of theory to artistic practice.

Bibliography

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000. Print.

##########################################################################

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles