One should question everything. At least I feel that I should question everything. It’s exhausting but I have no choice. The more that I question the more questions I have. It goes on and on. I’ve been this way since I was 3 or 4 – around the time I started playing guitar. It was curious to me. I loved the sound. You never know where sound will lead you and lately it’s been on my mind, “How did I get here?” I feel that I am part of a generation, or to put it more succinctly, part of a genealogy of 20th century American guitarists who reached deeply into traditions but were not bound by them. Questioning led me to scientific approaches, skepticism, and critical thinking. These perspectives and practices have fostered inspiration, enlightenment and self-realization.

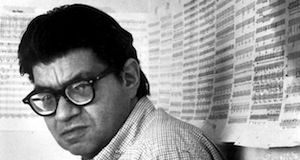

As a teenager I began playing jazz and much of my professional life has been as a jazz guitarist. Although I’d heard about composers John Cage and Morton Feldman by my late teens, I didn’t spend much time with their works because they were dismissive of jazz music. Consequently I chose to spend time with other composers and musicians who were more appreciative of jazz. As I got older and wanted to fill in gaps of knowledge, I spent time learning about Cage’s and Feldman’s music making processes. Conversations in the 1990’s with jazz pianist Borah Bergmann prompted me to dig deeper into Feldman’s work. A fine essay on Morton Feldman, “American Sublime” was written by Alex Ross and published in The New Yorker on June 19, 2006. A reprint of the article is posted on Ross’ Blog here. What follows are my thoughts, feelings and impressions upon reading some of Feldman’s writings.

Book Review

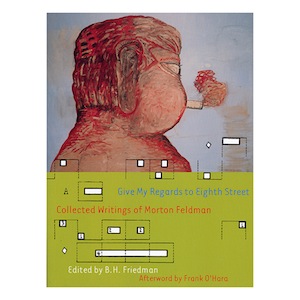

Give My Regards To Eighth Street:

Collected Writings of Morton Feldman

– edited by B.H. Friedman

When fellow composer Karlheinz Stockhausen asked Morton Feldman “What is your secret?”, Feldman replied, “I don’t push the sounds around” (143). This is revealing since Feldman’s sensitivity and lack of desire to “control” outcomes is a distinct part of his personal and compositional nature as we discover in “Give My Regards To Eighth Street – Collected Writings of Morton Feldman”, as edited by B.H. Friedman.

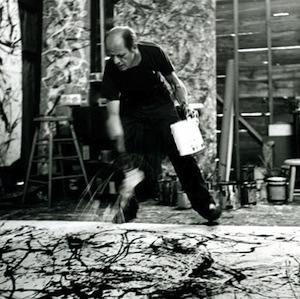

Relinquishing control of rhythm in painting was an approach that New York Abstract Expressionist painters adopted in response to Jackson Pollock’s “action painting” (84). Throughout the Introduction, by B.H. Friedman, and in many parts of the book, we learn that Feldman’s approach to music composition is informed by the medium of painting. Feldman expresses that New York painters were a stronger influence on his creative life than composers and that his friendship and affinity was with “Abstract Expressionist” painters including Pollock, Philip Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell (115). As a matter of fact, Guston’s painting of Feldman adorns the book’s cover.

Feldman mentions profound insights by painters such as when Rothko asked him while looking at a painting, “Is it there?…How much of it is there?” (178).

The point being, how much has to be painted in order for the “essence” to be perceived. This author imagines that Feldman felt similarly about his own music composition. Furthermore, in the essay, Between Categories, Feldman explores the distinction between subject and surface with specific respect to the works of early renaissance painter Piero della Francesca and post-impressionist painter Paul Cézanne (83-89).

While reflecting on della Francesca’s use of surface, Feldman sates, “Perspective is an illusionistic device, which separates the painter’s objects in order to accomplish the synthesis that brings them into relationship with each other” (84).

Contrastingly, Feldman notes that Cézanne leaves “little trace of a unifying organizational principle” (84). However this author would like to mention that Cezanne’s use of geometric forms is well known and, to note one example, we see the use of triangles as an organizational principle in the above painting “The Bathers”. Organizational principles demonstrate the type of control that Feldman has an aversion to. As he develops this rationale he concludes that his music is “between categories, “between time and space”, “between painting and music” and as such, “between the music’s construction, and it’s surface” (88).

Feldman is often associated with certain American, “New York School” composers including John Cage, David Tudor, Earle Brown and Christian Wolfe. Feldman studied with Wolfe and later became friends with Cage, Tudor and Brown.

Feldman discusses his first meeting with Cage in the lobby of Carnegie Hall after listening to Dimitri Mitropoulos conduct the New York Philharmonic in Anton Webern’s Opus 21, a symphony for small orchestra (114). It’s not surprising that Feldman shared compositional predilections with Cage, Tudor and Brown. Friedman mentions that from Cage, Feldman learned “about using chance in composition” and “the importance of silence as a negative Void (in the Eastern religious sense) rather than simply as negative space” (xix).

With respect to Eastern religions and practices, Feldman expresses his affinity with Zen Buddhism by telling traditional Zen student/master stories and aphorisms that correspond, in his eyes, with music composition such as “craft is something you do in the light, skill is something you do in the dark” (189-190). Somewhat provocatively, he convincingly uses Zen to criticize Cage’s statement, “Everything is music.” Feldman argues that once one states “what something is”, that person has defined another entities nature. Feldman relates, through telling a Zen story, that one who defines another entities nature has actually lost their own Buddha nature (29-30).

Feldman admiringly cites his preferences for Beethoven, Schubert, Edgar Varèse and his peers previously mentioned.

Feldman states that Beethoven’s late string quartet, the Grosse Fugue, is most revealing because it has “an aura of danger, of something gone amiss” (27). Feldman esteems Schubert’s use of register as a determining factor for where one or another melody is placed (190-191). He applauds Hindemith on questioning the definition of melody. About Cage, Feldman is impressed with the composers “self-abolishment”; the ability of the composer to let the music be itself (28-29). Another illuminating point Feldman makes, and one this author personally reveres, is “what really makes a composer distinguishable from another composer… is one’s instrumentation” (160). Unique instrumentation naturally expresses a distinctive group timbre, color scheme, and register range. When speaking about his own work, Coptic Light, he recounts how Sibelius’s observations influenced orchestral nuances in varying color and a sense of “chiaroscuro” (201). As Feldman wonders about orchestration he cautions against the way that “Webern revealed his structures”, the way he presented ideas, through his orchestration (191). Furthermore, as Feldman talks about the relationship between orchestration and color, he references Titian and Matisse to underscore his perception of the former’s craft and the latter’s skill (192). Correspondingly, Feldman does not consider the orchestrations of Schoenberg or Webern to be colorful (192). He calls Schoenberg’s Erwartung “a total field of sonic consistency” (196).

Feldman senses that twentieth century music is too strongly bound to tradition (209). He sees virtue in works that are a bit out of control (27). Feldman feels that composers have allowed themselves to be controlled by the forces that dictate western music historiography. He concisely states, “the less control, the less music history” (209).

Feldman’s definition of composition is “the right note in the right place with the right instrument” (160). He also expresses a penchant, which he learned from Kafka, to begin the piece “immediately in the atmosphere” (163). In “String Quartet” his primary theme is “duration” (133). Feldman mentions that it took him three months to compose the work and that the most familiar aspect of a composition is it’s duration. Perhaps as a way to undermine a listener’s expectations of development and ultimately the works conclusion, Feldman composes to displace the listener’s sense of time. He does this by guiding the listener with “chronological information” as an aid in understanding the “story”. This is in contrast to the more commonly employed “cause and effect” syndrome. In another essay Feldman mentions his desire to “take away” material in the course of a piece (175).

Feldman is perpetually condescending towards a few composers including Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Arnold Schonberg, Anton Webern, Igor Stravinsky, and Olivier Messiaen. His view on these composers illuminates his aversion to specific compositional or orchestration practices. For instance, Feldman likens Olivier Messiaen’s orchestrations to “Disneyland” and “Technicolor” (160). Furthermore, Feldman criticizes Boulez for not conducting experimental music. Feldman calls Boulez’ programs “glamorous samples of things done first somewhere else, with a known reaction” (120).

Also in this book are a variety writings that were unpublished in his lifetime along with an Afterward by the writer, poet and art critic Frank O’Hara who emphasizes the unpredictability, sensitivity and spiritual connotations of Feldman’s compositions (211-217).

Disappointingly, for this author, the only reference to jazz in the book occurs in the introduction where Friedman quotes Feldman saying that jazz is “too easy” (xiv). Aside from the fact that his dismissive remark is ignorant, insulting and shallow, I am surprised by Feldman’s lack of interest in jazz especially because he often expresses interest in artistic expression that is not bound by organizational principles (74), where spontaneity is welcomed through improvisation (43), and that successful music has tone that people can relate to combined with a sound that has an affinity with the tone (74).

Regarding the first point, Feldman’s lack of curiosity in New York City based (where Feldman lived), cutting edge, jazz artists such as Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, or Albert Ayler demonstrates a myopic ignorance of jazz contemporaries who composed and improvised using new organizational principles that are simultaneously flexible. Furthermore, his last point is especially relevant to the field of jazz where a primary goal of master jazz musicians is the development of a “personal sound”. Additionally, this author finds it curious that Feldman doesn’t reflect on female composers or writers for inspiration and rarely on female painters.

Feldman does mention French novelist and memoirist George Sand (Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin) but only with reference to Flaubert (31). He does cite the painter Joan Mitchell as a friend without mentioning any specifics (97). About the work of dancer Sybil Shearer, Feldman called her work “one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen” (177). Feldman wrote a brief essay about painter Sonia Sekula and said, “she was very gifted, that little spice that added to the scene tremendously” (102). However, he did compare Sekula to Elisabeth Bergner (94). It’s interesting to note that none of his male composer or painter friends necessitates comparison with other contemporaries. Finally, other than academic ‘western European” art music, the music of a few American mavericks like Charles Ives, Henry Cowell and Varèse, and the music composed by those in his circle, Feldman does not express interest in music found from any other world culture.

There is a sense of nostalgia in these essays that speaks passionately about artistic issues. I wish I had met Morton Feldman. Too bad the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village, where he and his associates talked about art, is no longer in business. All that is left now is music and mythology. However, the sensitivity of his essays with their inherent strength of tone has sparked this author’s curiosity about re-investigating the delicate beauty of Feldman’s music; a music that is not “pushed around”. The essays in this book point to the value of understatement which is refreshing in contrast to the contemporary mainstream values of “extreme” gestures, grandstanding and ostentatious displays of exaggeration that are employed to intimidate, cajole and coerce emotions as though people need to be “shocked and awed” in order to feel . . . . . . .something.[i]

[i] This is a reference to The Shock Doctrine – The Rise of Disaster Capitalism by Naomi Klein.

Bibliography

Feldman, Morton. Ed. B.H. Friedman. Give My Regards To Eighth Street. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change, 2000. Print.

Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine – The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, NY: Picador, 2007. Print.

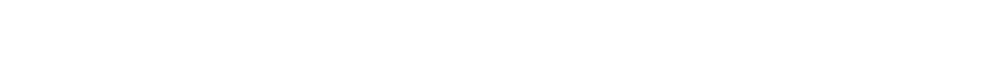

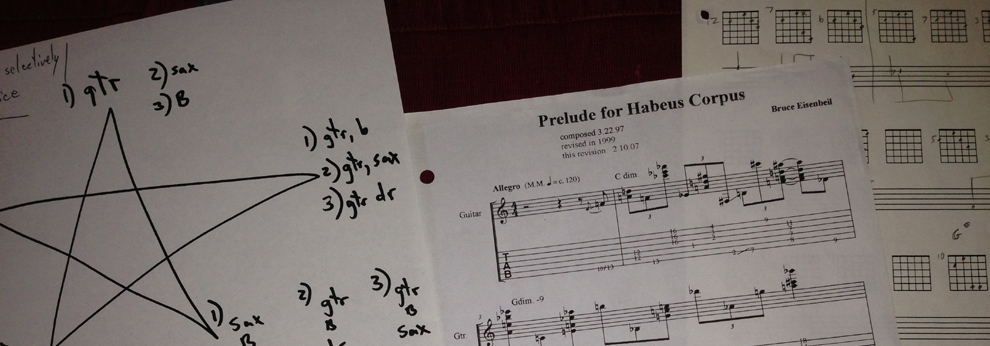

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles