Although I was born in Chicago, I was raised in New Jersey. I grew up at the end of a dead end street. As a kid in Plainfield , NJ in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, my friends and I ran around the neighborhood visiting our neighbors, many of whom were first or second generation immigrants from around the world. Being a skinny kid, my friends mothers wanted to fatten me up. Every place I went I was fed. And every house had different music being played. So I heard music from many places in the world. I remember enjoying traditional Irish music, Louis Armstrong, Top 40, R&B, Motown, Tito Puente, The Beatles, Tom Jones, Wes Montgomery, Bossa Nova, Swedish folk songs, Allen Toussaint, Dr. John, classical music, 1950’s Doo-Wop and rock and roll, and more.

As a teenager, now living in a rural area of NJ, I visited local libraries to read about and listen to more jazz than I could ever find at nearby stores. Additionally, I also borrowed music anthologies released by The Library of Congress and The Smithsonian Institute. These anthologies focused on music from various parts of the world. I enjoyed these recordings and learned a bit about the music from the liner notes and learning songs by ear. Some of these recordings were engineered by scholars trained in ethnomusicology. However, most of these recordings were older than the established field of ethnomusicology and thus were made in a predecessor discipline such as comparative musicology or folk song studies. Although the distinctions are significant with respect to the scientific and cultural conditions employed during the learning and transmission of the research, it is not the purpose of this paper to delve into those distinctions here. Future essays will.

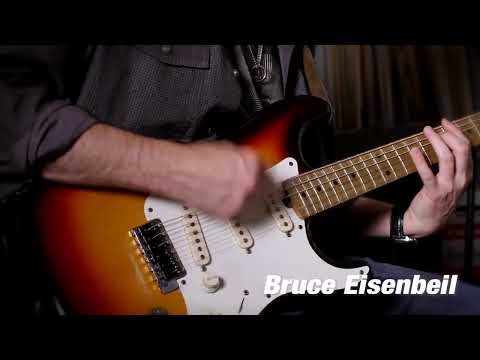

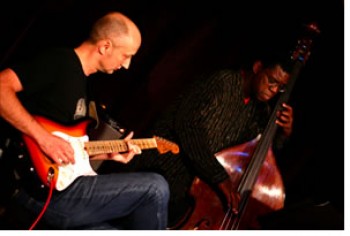

This is the first of three papers originally written in the fall of 2011 for a course called, “Native American Perspectives in Music”. As a prerequisite for this course I studied Anthropology. My ‘go to” text was Anthropology: A Global Perspective by Raymond Scupin and Christopher R. DeCorse. Anthropology has four core subfields most often related to work done through universities and museums – Physical Anthropology, Archaeology, Cultural Anthropology/Ethnology and Linguistic Anthropology. Another new subfield is Applied Anthropology. Each subfield has a variety of specializations; far more than can be stated here. However, subfields of Physical Anthropology include biological, primatology and human ecology. Subfields of Archeology include prehistoric, classical and biblical archaeologies. Cultural Anthropology includes demographic, economic, social and political studies. Linguistic Anthropology includes structural, historical and cognitive linguistics. Applied Anthropology is another subfield that addresses modern problems and concerns that are often outside universities and museums. Examples include Forensics and those previously mentioned who use their knowledge in government or private sectors. Some music practitioners may not know that anthropological perspectives are the basis for ethnomusicology which is itself a subfield of cultural anthropology. In 1964 Alan P. Merriam published his book The Anthropology of Music, where he outlined and developed a theory and method for studying music from an anthropological perspective using anthropological fieldwork methodology. Future essays published here will speak to Merriam and other ethnomusicologists as well as the historical development of this field. For now, suffice to say that ethnomusicology is the study of how people make and use music around the world. Having been a professional musician since I was 15, over 36 years now, I was aware of the many ways that rock, blues and jazz musicians make and use music. However, through learning anthropological perspectives, which are also the basis for theoretical cultural studies, the scope and breadth of my understanding of world cultures and specifically, Native American cultures, widened considerably. This new knowledge has immeasurably informed my rubric of musical understanding and I feel that as this knowledge informs me, I am a better performer, composer, and music educator. The diverse richness of perspectives I learned is a wellspring that informs my ever-expanding horizon of creativity.

Understanding Native American Music Across the USA (Part 1)

“Songs are thoughts, sung out with the breath when people are moved by great forces and ordinary speech no longer suffices” – Orpingalik[1]

The historical and contemporary practice and use of music in culturally diverse Native American communities is rich and ongoing. This review focuses on two books and a variety of recordings. Specifically, we will look at the key points in the preface and introduction of a geographically based case study, Beverley Diamond’s Native American Music in Eastern North America. We will also explore the introduction and first two chapters of an anthology of scholarly case studies, Tara Browner’s Music of the First Nations. Each book reflects on the history of anthropological and ethnomusicological theory and practice noting relationships and processes. They inform the way Native American music is represented. Additionally, by exploring musical pieces from the CD accompanying the Diamond textbook, we will observe the similarities and differences that exist in Native American music.

As this author learns more about anthropology and ethnomusicology, the importance of stating authorial challenges and partiality as a way to establish theoretical perspective for readers becomes more apparent. One of the key points discussed in the preface and Chapter 1 of Diamond’s book is acknowledgement of her observational strengths and weaknesses. For example, she describes the challenges of writing about the wide scope of Native American music cultures when she states, “the cultures of the more than five hundred nations are distinctive and unique…” (xiii). Diamond mentions that she struggled with the decision to take on this writing assignment because she feels that members of the Native American cultures are able to speak more eloquently than she, an outsider. Diamond’s Native American colleagues emphasized that “knowledge carries with it obligations and responsibilities” (9). As music has a variety of functions in any given culture it is important to recognize implicit in these functions is the responsibility of the participants to understand the implications of the knowledge and that one must be able to express how the knowledge should be used. Diamond lets us know up front that the Northeast is covered in more detail than the Southeast because her experience, and that of her advisors, is located there. Another weakness she describes is the clear need for indigenous perspectives, which is amplified by the “relative sparsity of ethnomusicologists of First Nations, Métis, or Inuit descent” (xiii). One strength Diamond discusses is that she sees her role as two fold, “to share the knowledge that I have but also to enable a dialogue about the representation of indigenous music in the academy” (5). Diamond’s Native American primary advisors are a clear observational strength; these three wise people who function as an advisory committee in the writing of this book, bring first culture perspective. Diamond notes the need for dialogue that “does not gloss over the shared responsibilities that we have toward social justice, the environment, and peaceful coexistence” (xiv).

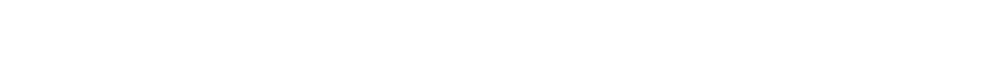

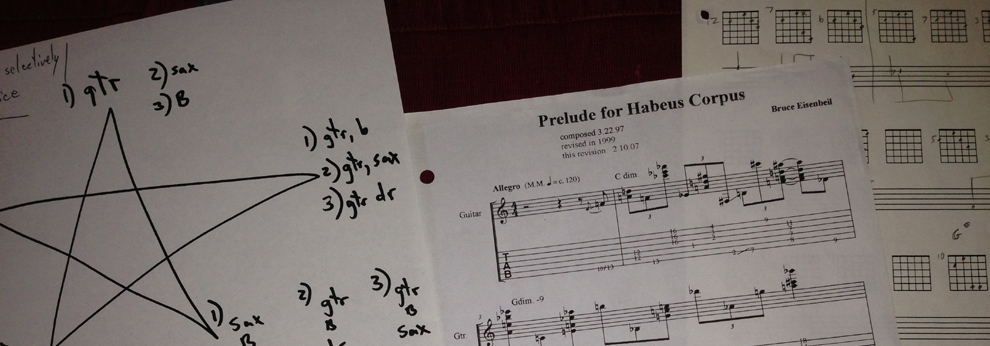

Another challenge Diamond discusses is “the mismatching of languages for concepts that, in English, we call ‘music’, ‘song’, etc.” and the reductionism that inevitably transpires due to the problems of musical notation and musical representation (xiv). Diamond mentions, “ ‘music’ is a noun that fails to convey the processes and relationships that singing and drumming embody in many Native American contexts” (25). As this author learns about Native American perspectives it becomes problematic to use the term “music” in this essay because as Diamond notes, there are no words in most Native American languages for “music”. This author was impressed that Diamond brought up the challenges of music notation, specifically the “subtleties of timbre and pulse notation”, as these specific subjects are primary constituents of my musical interests and compositional aesthetic. Although it is not this author’s intention to further illuminate personal musical and compositional interest in this paper, rest assured that these personal interests will be expanded upon in future essays.

Diamond addresses her goal of demonstrating “how musical practices have often developed in response to social circumstances, to colonialism in particular” (xiv). These practices demonstrate the ways that people are motivated to express themselves musically as three themes – traditional indigenous knowledge (TIK), encounter, and indigenous modernity – are used to address the challenges of these practices. These points are more explicitly laid bare through questions she asks, such as, “Who claims TIK and for what purposes?”(12). Diamond notes the endemic appropriation of TIK for purely selfish commercial motives by suspect producers. Encounter functions as a pro-active learning perspective. Sound and song traditions of Native Americans make the most sense when they are considered as part of an encounter with different natural and social spheres. In this way, the sounds of specific localities, and the sounds of song traditions from neighbors or foreigners inform one’s awareness, experience and knowledge. The encounter encourages comparison between different ways of learning music. For a culture to thrive it is imperative that expressions of indigenous modernity be communicated as a way to challenge the stereotypes that are expressed from the romanticisation of colonialism which tends to render the cultures obsolete, as though in a static timeless past.

Contemporary Native American artists also use legends. Diamond’s comment, “legends teach us that accidental and unexpected incidents in our lives are important teachings” has high value because as a performing musician, this author believes that improvisation is culturally important as this author prefers to live in a world that embraces spontaneity, accidental, and unexpected incidents (13). Legends are an oral performance of a narrative, which express TIK through man’s environmental and social relationships. Diamond notes “legends may encourage listeners to use their minds and to make ethical decisions for themselves” (13).[2] Visions of modernity are expressed as new generations learn traditional teachings and use them in their own way, renewing the way that legends are transmitted. Diamond lets us know that, “Replacing names in colonial languages with names in indigenous languages is part of the process of asserting a vision of modernity for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people” (5). Additionally, transmission is renewed in a variety of contexts in that “in recent decades, the great legends have been maintained by puppet troupes, playwrights, musicians, dancers, and filmmakers” (14). As traditions are explored and reevaluated, contemporary forms of expression empower indigenous peoples to reshape and renew cultural identities. As we shall see, specific case studies illuminate these points in greater detail.

Part 2 of this essay, along with end notes and bibliography, will be posted next week.

- Intro Guitar Technique and Advanced Guitar and Performance Techniques - May 30, 2016

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #6 of 6 - April 15, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #5 of 6 - March 31, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #4 of 6 - March 11, 2015

- Western Music History From Antiquity Through The 18th Century - March 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 25, 2015

- Native American Perspectives in Music – Post #3 of 3 - February 18, 2015

- Critical Theory And The End Of Noise – Post #3 of 6 - February 11, 2015

- Music Theory And Harmony - February 4, 2015

- Anthropology of Music – Post #2 of 3 - January 28, 2015

Social Profiles